July 14, 2014

Four reasons why using EI Premiums to balance the budget is bad for the country—and Ontario in particular.

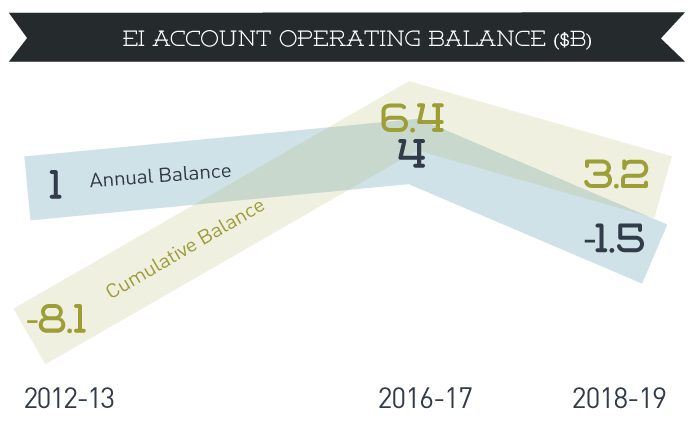

As the Parliamentary Budget Officer has pointed out, EI premiums will not be lowered, despite the fact that the EI operating account will have replenished past deficits by 2015. EI premiums have been increased three times since 2010, following a dozen years of steady decreases.

So in order to balance the budget, the federal government is in fact carrying out a regressive tax increase. Here’s why balancing the budget using Employment Insurance premiums is a bad idea.

1. They are not an efficient (or fair) way to raise revenue

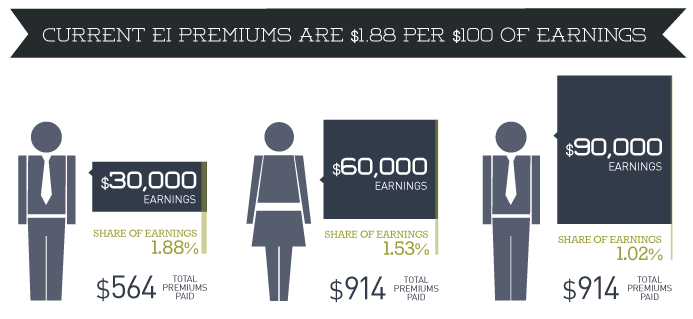

EI Premiums are payroll taxes. In addition to an individual worker’s contribution, employers contribute an amount equal to 1.4 times the employee’s contributions. On balance, payroll taxes are more likely to have a negative effect on employment (especially for lower-income workers) than other (less distortionary) taxes, such as the GST/HST or income taxes.

2. They are regressive

EI only covers earnings up to a certain amount. In 2014, that’s $47,600. Employment earnings over that amount are not insured. That’s why premiums are only collected on payroll earnings up to that amount. This means that lower-income workers pay more as a share of their earnings than higher income workers. Instead of just funding an insurance system for involuntary job loss, the government is balancing its books – and funding other programs like health care and national defense – by increasing taxes on those who can least afford the burden.

3. They are hidden

The federal government has not been very forthcoming about the starring role EI premiums are playing to help balance the budget. Here’s how the government describes its plan to return to balance in Budget 2014:

In keeping with commitments made at the beginning of the economic recovery, the Government’s plan to return to balanced budgets has focused on controlling direct program spending by federal departments, rather than raising taxes that are harmful to job creation and economic growth.1

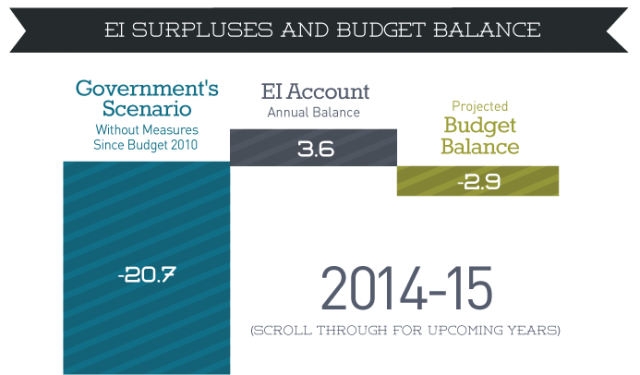

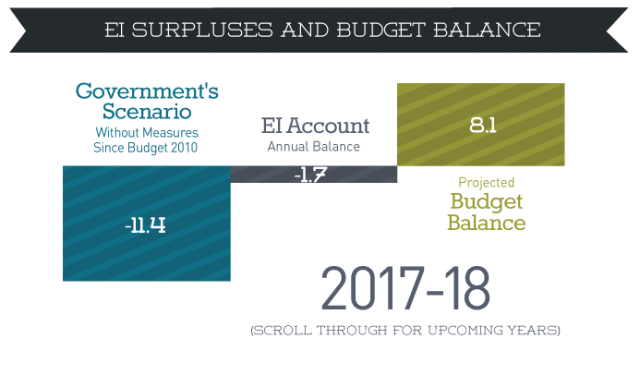

However, if you look at the government’s own estimates of what it will take to close the budget gap, the surplus in EI Premiums is responsible for one fifth of the effort to balance the budget.2 The pressure is only projected to ease off when EI premiums are scheduled to decline in 2017-18. The government should be more forthright about how it’s achieving a balanced budget using EI premiums.

4. EI Premiums are just making a broken Employment Insurance system worse

The Employment Insurance program is plagued by a number of well-documented problems that undermine its equity and effectiveness as an insurance program.

As eligibility for the program has failed to keep pace with the changing nature of work, fewer than 40% of Canadians that find themselves unemployed today qualify for EI benefits. This declining coverage is not evenly distributed across Canada. Lower eligibility in Ontario has meant that the province’s residents and businesses have consistently paid more into Employment Insurance than they get back—a net total of $20B from 2000 to 2010. 42% of the country’s unemployed workers originated in Ontario, but just 32% of them were receiving EI benefits over the last two years. The payroll tax that is being raised is one that is punitive towards Ontario.

Conclusion

While the current federal government’s policies have mostly been consistent with the view that lower taxes—especially payroll taxes—are important for economic growth and job creation, using higher EI premiums to raise revenue beyond the needs of the program is a significant and problematic exception. There are four problems with increasing EI premiums to raise revenue for other programs: it is economically inefficient, it lacks transparency, it is regressive, and it makes the well-known problems of the EI system worse, such as the fact that it redistributes funds away from Ontario.

This is not an indictment of all payroll taxes—the Canada Pension Plan for example, is an entirely different matter with a different rationale, economic impact, and financial management. Raising a surplus through EI premiums is a uniquely troubling approach and it’s particularly unfair to Ontarians.

We’ve seen this story before, when the federal government used EI surpluses on a much larger scale through the 1990s and early 2000s to improve the overall budget picture. While some policy changes since that time have reduced the chance of surpluses of that magnitude happening again, they have not prevented a return of the ill-advised use of EI contributions as a budget-balancing tool.

To protect against these problems, the government should fully separate the Employment Insurance operating account so that revenues cannot be redirected to general revenues. As it stands now, the fund is only separate for reporting purposes. A fully segregated fund with a break-even rate for premiums would prevent federal governments from using the EI fund as a convenient but opaque and unfair way to find extra money.

— Noah Zon

Related research

Cheques and Balances

This looks at how regional redistribution works in Canada through the federal government.

View this paper

More related to this topic

- Pg. 244. http://www.budget.gc.ca/2014/docs/plan/pdf/budget2014-eng.pdf [↩]

- The fiscal “effort” describes the revenue increases and cost savings that would be needed to balance the budget, in comparison to a “business as usual scenario” if none of the actions to reach budget balance since 2010 had been put in place. Using 2010 as a basis of comparison (as the government does in their budget documents) will tend to make the gap look larger than it would otherwise given that there were large temporary bursts in spending for economic stimulus that year. [↩]