May 29, 2014

On May 29, 2014, Mowat Centre Director Matthew Mendelsohn provided expert testimony to a House of Commons Standing Committee, as they study the $2B annual Labour Market Development Agreements. His speaking notes, found here, highlight the ways the program has failed to keep pace with modern labour markets, and how its design unfairly penalizes Ontario.

Introduction

Good morning Mr. Chair and members, and thank you for the opportunity to present to the Standing Committee as part of your study into the Labour Market Development Agreement.

One of our main areas of focus at the Mowat Centre is to look at how federal public policy can better contribute to Ontario’s prosperity. That mission will inform my remarks today.

For that reason, I was very pleased to learn that the committee would be studying the Labour Market Development Agreements, which have not kept pace with evolutions in our labour market, particularly in Ontario. I should note that as Ontario’s Deputy Minister for Intergovernmental Affairs, I participated in the negotiation of the Labour Market Development Agreement, the Labour Market Partnership Agreement, and the Labour Market Agreements.

In particular, I’d like to highlight three main points for the committee during my testimony today.

- That the changing nature of labour markets requires a change to our policy responses, particularly in the Employment Insurance system.

- That the approach to allocating federal funding under the LMDA unfairly punishes Ontarians; and

- That meaningful improvement to the LMDAs can only happen through better partnership with provincial and territorial governments.

Theme 1: Changing labour markets

The Employment Benefit Support Measures or EI Part II benefits were set up in their current form in 1996. In the almost twenty years since, eligibility for the training and employment services funded under this program have not changed significantly.

In the same period, we’ve seen tectonic shifts restructuring our labour markets and changing the nature of work in Canada.

In Ontario, since the year 2000 we have seen a declining share of employment in manufacturing (from 18% to 11% in 2013) and an increasing share in service sector employment (from 73-79%)

Fewer people can rely on permanent, full-time employment in the past and the protections that come with that work, including access to the protections of the EI system and the training opportunities that flow from inclusion in the EI system. Growth in part-time work has outpaced full-time employment in Ontario, and one third of Ontarians who work part time are doing so because they cannot find adequate full-time work.

This restructuring has also led to troubling new levels of long-term unemployment, particularly for those left out of the recovery in the wake of the recession.

In a perverse and unintended outcome, this restructuring has not only meant that more Ontarians are in need of support to adjust to new economic realities, but that fewer resources are available to them. Fewer resources are available because they are outside the EI system, the key determinant for whether workers have access to most training programs funded by the federal government.

Employers generally have shown themselves to be unwilling or unable to invest in the type of training that is necessary to bridge skills gaps for the vast majority of these unemployed workers, especially those who have been unemployed for longer periods of time. This is a problem because more and more Canadians are outside the EI system, yet most federal training funds are tied to EI eligibility.

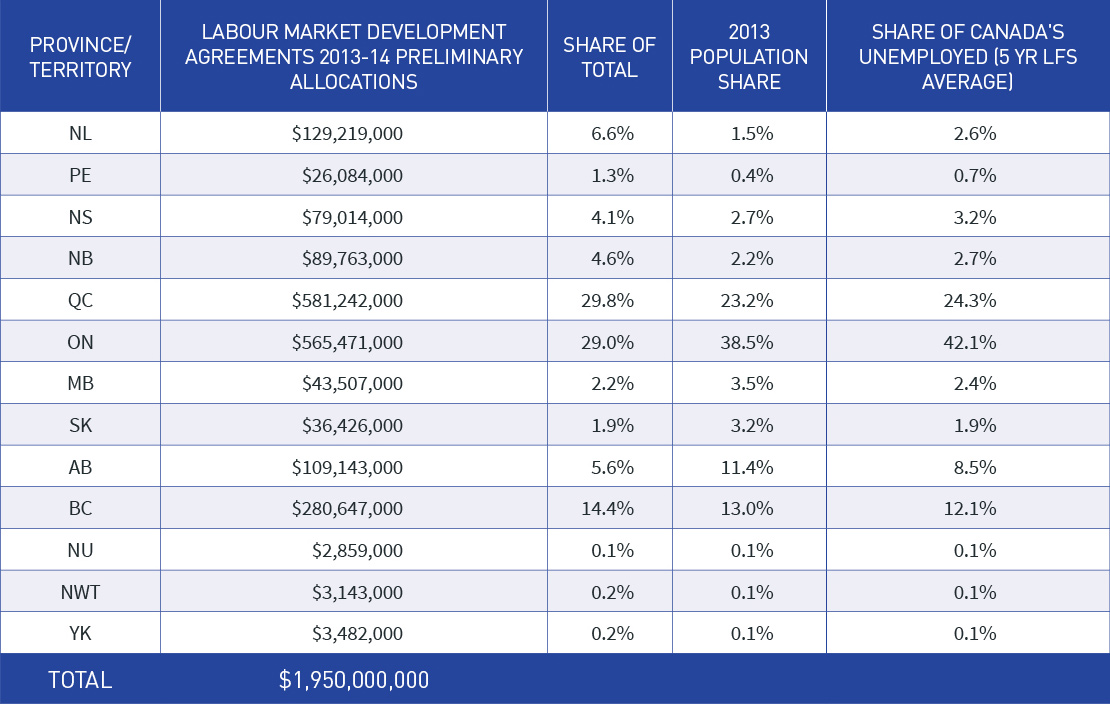

The $1.95B nationally in federal funding for skills training and employment supports through the LMDA represents the largest program of its kind in the country.

Eligibility for this training funding remains tied to whether or not someone qualifies for Employment Insurance, a program which simply has not kept pace with changing economic conditions and labour markets.

The result is that these programs only serve about 37 per cent of unemployed Canadians and only about 28 per cent of unemployed Ontarians.

42% of unemployed people in Canada and 39% of Canada’s total population currently reside in Ontario. Despite this, Ontario received only about 29% of the $1.95B in LMDA funding last year.

Theme 2: Federal allocation formula discriminate against Ontario workers and businesses

Some of those labour market changes I discussed have been felt particularly acutely in Ontario.

However, far from providing additional support to the province during this period, far from helping to moderate these changes or provide supportive adjustment funding to workers and communities, the LMDA federal funding formulae have remained stuck in the past.

Ontario received only about 29% of the $1.95B in LMDA funding last year. This is of course far lower than the province’s share of the Canadian population (39%) or Ontario’s share of unemployed people in Canada (42%).

This allocation is based on no fair rationale, nor is the allocation formula even explained publicly.

One of the main reasons for the skewed distribution is that $800M of the total funding commitment for the LMDAs is allocated between provinces based on the relative impact on different provinces of EI reforms in 1996, the same time that the federal government shifted most of its training funding out of regular spending and into the EI system.

Ontario’s share of that $800M has been fixed at 23 per cent. Today’s 18 year olds entering the labour force faces a policy environment explicitly designed to deal with a world from before they were born, just as NAFTA was being implemented. This is patently absurd – and it is scandalous that no federal government has moved to correct this injustice felt every day by workers in Ontario looking to upgrade their skills.

This also means that even though EI only covers a small percentage of Ontario’s unemployed, Ontario still receives a lower amount per beneficiary.

It’s worth keeping in mind that Ontarians continue to pay premiums at a rate comparable to their share of the population, meaning that they continue to make an outsized contribution to an insurance program that they are increasingly not eligible for. Between 2000 and 2010, Ontario workers and businesses contributed $20 billion more in EI premiums than they received in EI benefits.

To state it another way, as of 2012, Ontarians were paying 40 per cent of EI premiums and receiving only 33 per cent of income benefits and 28 per cent of LMDA funding from the EI account, despite having above average unemployment.

It is perfectly acceptable that provinces with low unemployment pay more into the EI system than they get back. It is patently absurd that provinces with above average unemployment pay in more than they get back.

Theme 3: Partnership with provinces

Third, I’d like to focus on something that we’ve seen work relatively effectively under the LMDA, and that’s the partnership with the provinces.

The main feature of the changes in 1996 that set up the Labour Market Development Agreements was an explicit decision by the federal government to step back from direct involvement in the delivery and management of labour market training.

That wasn’t to say that the federal government no longer found it a priority to invest in human capital. But the move to create the LMDAs and fund federal training through part II of the EI Act was a recognition that the provinces and territories were better suited to delivering these training programs alongside their related services.

Over the course of the following 13 years, the federal government was able to negotiate agreements with all of the provinces and territories to transfer the funding and responsibility for these programs.

In Ontario, this agreement was an important driver in the province’s move to integrate its whole suite of employment services, most of which are delivered by institutions in the community. Overall, the transfer of services to the provinces worked well and evaluations have found that this transfer has resulted in more seamless access for clients.

The federal government has expressed an interest in looking at ways to improve the results achieved by training funding across its programs. That is to be commended. A focus on results, employer engagement, and transparent reporting is important to any renewal agenda.

However there are right and wrong ways of approaching that renewal.

No matter what one thinks of the Canada Job Grant in particular or greater involvement of employers in the design of training programs in general, it would be hard to argue that the year long fight sparked by its surprise announcement – and expectation that 2/3 of it was intended to be funded out of existing federal transfers to provinces and provincial revenues – was a productive way for governments to meet the needs of Canada’s unemployed or invest in our human capital.

Provincial and territorial governments have built long-standing relationships with non-profit and institutional partners in the sector. They have built suites of complementary programs to ensure a continuum of programs are available to those looking for work.

Improvements can be achieved to employment and training services in Canada without throwing that sector into disarray and I would urge the federal government to avoid repeating the mistakes it made with the introduction of the Canada Job Grant.

Solutions on these issues are clear:

- Make it easier for provinces to use the LMDA funding to help unemployed Canadians regardless of whether they qualify for employment insurance.

- Move more of the federal training dollars into Labour Market Agreement style transfers so workers other than those eligible for EI can access training.

- Update the 1996 allocation formula so that Ontario’s unemployed have as much opportunity to upgrade their skills for new jobs as Canadians in other provinces.

- Work with provinces – rather than against them – to implement employer-based trained programs consistent with the goals of the Canada Job Grant.

Presentation Date

May 29, 2014

Audience

House of Commons Standing Committee

Author

Matthew Mendelsohn