January 16, 2015

Canadians have the right to information about work done on our behalf and paid for by our taxes.

This right is a key part of government accountability in a democracy, and it’s enshrined in the federal Access to Information Act.

Naturally, there are some reasonable exceptions, such as: anything that is part of the deliberations of Cabinet or information that, if released, would cause harm to national security. The exceptions depend on some degree of judgement, so officials have discretion on which information to disclose.

Last summer, there was a lively exchange in the National Post between federal Finance Minister Joe Oliver and Mowat’s Matthew Mendelsohn about transfer payments to Ontario. Matthew and the Minister disagreed on whether Ontario missed out on $641 million when the federal government canceled Total Transfer Protection payments.

As evidence-obsessed researchers, we wanted to learn more about the policy and its genesis. So we filed an Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) request for Finance Canada briefing material. In fact, we filed two requests—but more on that later…

We believed that we would get some useful information from these requests. We were wrong. Here’s the cautionary tale of what happened when we filed an ATIP request.

Like a throwback to the days of rotary phones and punchcard computers, the federal government required a paper request form outlining the specific documents requested, along with a $5 cheque or money order for each request. The Mowat Centre doesn’t have a chequebook, and given that a money order would have been more expensive than the request itself, we wrote a personal cheque.*

From the time a federal department receives a request, it is required by law to respond within 30 days. This is not the same thing as completing your request. However, response time is reset each time the department requests clarification or recommends reducing the scope of the request (in our case, we received warnings that our request could require many months and several thousand dollars to complete.) So we made a few concessions, agreeing to exclude emails and drafts, and agreeing to receive information as it became available rather than in one large dump. By late September we had finalized our requests, and sent two $27 personal cheques to the Department of Finance. Then we waited excitedly for the day our information would arrive.

After all the negotiation, what did we actually get? Lots of redaction and no satisfaction.

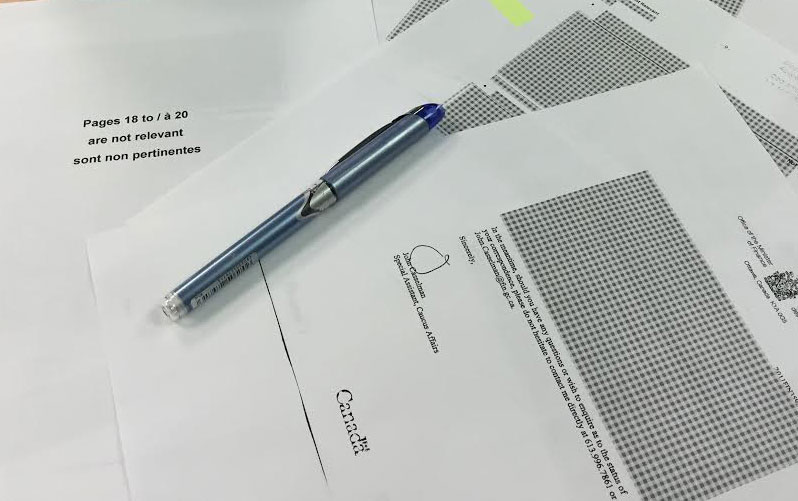

As of January 12, 2015 we’ve had a partial response to one of our requests, while the other has been completely ignored. For our request regarding Total Transfer Protection we have received two compact discs (yes, they still exist) with a total of 190 pages of PDFs. Those documents were so heavily redacted you’d think that we’d stumbled on the Canadian version of the secret military weaponized Dolphin program.

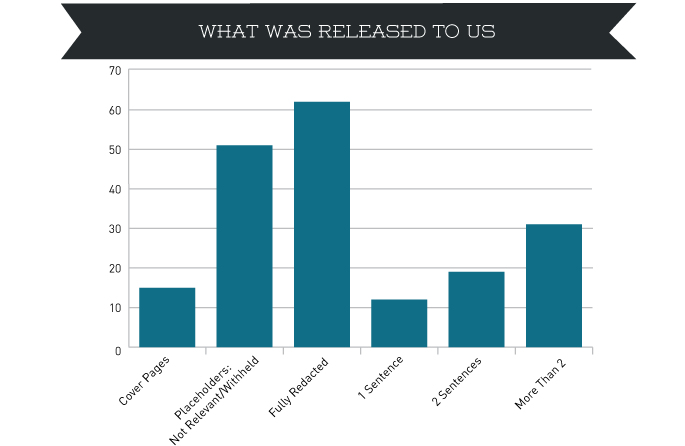

In the absence of new information to analyze, we analyzed what wasn’t there.

The chart below shows how the documents we’ve so far received breaks down. Two-thirds of the pages on the CD contained zero information—they were cover pages (8 per cent), fully redacted pages (33 per cent), or they were pages inserted to inform us that the real pages had been removed (27 per cent). Only 16 per cent (or 31 pages) of documents had more than two sentences of actual content. A further 16 per cent of the pages contained one or two sentences of un-redacted content.

Obviously governments need to be able to operate privately for some of its business. But a result like this goes well beyond reason, and our experience is hardly exceptional. Nor is this type of result much different when filing requests with provincial governments. Citizens should have easier access to more information in a way that is more efficient for everyone involved.

Here are a few ways to make that happen.

1. Make information publicly available by default.

Bureaucrats should be required to make the case for exclusion of material from the public. Instead of carefully choosing what information to release, governments could move to a “disclosure by default” approach—an idea raised in Mowat’s work on behavioural insights. This means flipping the tables so that it is the norm to make documents publicly available to begin with, rather than the reverse. Municipal governments already have significant amounts of public service advice made available publicly as advice to council. There is no reason this couldn’t be true for federal or provincial governments.

2. Once something is available to someone, make it available to everyone.

When government officials respond to an Access to Information request, they invest considerable taxpayer-funded effort to sort through information and analysis that was also funded by the taxpayer. Making these documents available freely on the internet, after a modest waiting period that would allow journalists a chance to do original reporting on their own efforts, would save time and provide more value for money. The federal government has taken some steps in this direction by listing completed requests and letting you request those documents. Why not eliminate this extra step and make it all available?

3. Design the Access to Information system around needs of the users of information.

The current system is the opposite of citizen-centred. Nothing is intuitive. It is so complicated that two journalists recently wrote a book on how to navigate the process. It could be made much easier by letting users make requests from more than one ministry at the same time, by providing clear instructions on how to find the information you’re looking for, and by allowing the entire request to be navigated on the web (rather than mailing out expensive photocopies or CDs).

The Access to Information Act is so archaic when it comes to technology that it has a fee schedule that refers to “$16.50 per minute for the cost of the central processor and all locally attached devices”. Thankfully, we no longer need computers the size of boardrooms to share data. Modernizing the ATI process would have the dual benefits of delivering much better service to Canadians while saving their governments a great deal of money through reduced administration costs. Smart design is not a luxury—it’s part of good governance.

*Since the time that we made this request, Finance Canada has mercifully joined the ranks of federal departments participating in the online request and payment system.

UPDATE (January 20, 2015):

While we were writing this post, we decided to test another part of the Access to Information system. The federal government allows you to search a list of already-completed requests for information and make a request through an online form for the same files without going through the same formal process (or pay those costs). We found one where someone had asked for briefing notes from 2013 on the impact of hydroelectricity on the Equalization program. We received this—what the Department of Finance called “disclosed in part”. At least in this case we got our blacked-out documents fairly quickly.

— Noah Zon