June 4, 2018

It’s a familiar feeling. You need something. You invest resources – time and effort – to get it. You finally see it in front of you. You reach for it. And… you realize there’s still a barrier preventing you from grabbing and using it.

This is the reality faced by researchers and government officials looking to understand whether our secondary and postsecondary education system is providing students with the skills they need to succeed in the economy of tomorrow.

A new era of skills data

Canada has an enviable rate of secondary school completion and postsecondary education attainment. But how well does that translate into the workforce?

This question is not as simple as it might seem. To answer it we need reliable data, for example, about:

- Labour market outcomes relative to different education pathways and types of skills training (e.g. apprenticeship training, private career college, public college, undergraduate university, postgraduate university).

- The distribution of skills in the labour market and the returns to particular skills in the context of technological change (e.g. digital skills; problem-solving skills).

- The education pathways and labour market transitions of populations of interest (e.g. youth, immigrants, Indigenous Peoples, persons with disabilities).

- The success of skills retraining policies (e.g. upskilling; retraining of displaced workers; return of women to the labour force).

To succeed in this economic reality, the students of today – the workers of tomorrow – must develop the skills needed to manage an information-intensive digital environment.

Historically, such data has been hard to come by. It requires moving beyond one-time snapshot surveys to a more longitudinal tracking of students-turned-workers through time and over the course of the life cycle. It also requires a way of measuring peoples’ skills that goes beyond respondents’ subjective self-assessment. And it requires samples large enough that the effects of other variables potentially affecting labour market outcomes – for example, whether one got married and has kids, or encountered health problems – can be statistically accounted for.

Obviously, this is very expensive and labour intensive to do. The good news is that governments in Canada were able to work together and make the investments to generate that data. The bad news is that the complexity of this new data also makes it challenging to access and use.

Skills data today: we have it, but it’s still out of reach

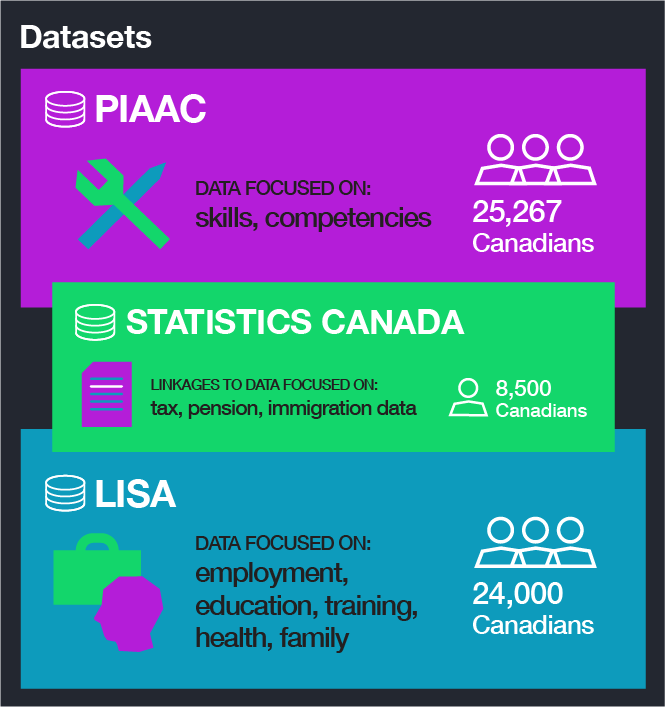

Earlier this decade, Canada participated in the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). PIAAC, rolled out in 34 countries between 2011 and 2016, was a study that directly assessed the competencies of adult Canadians (ages 16-65). In Canada, PIAAC was then followed by the Longitudinal International Survey of Adults (LISA). LISA has collected information on employment, education, training, health and family every two years since 2012.

Canada’s federal, provincial and territorial governments invested in having a much bigger PIAAC sample than the other 33 participating countries. PIAAC surveyed 25,267 Canadians, compared with a standard sample of 5,000. LISA surveyed 24,000 Canadians – also a very sizeable sample. Around 8,500 respondents in Canada were included in both surveys. And both surveys collected identifying information from respondents, which has enabled Statistics Canada to link the respondents included in both surveys to their tax, pension, and immigration data.

All of a sudden, researchers and policymakers had at their fingertips a wealth of information about a variety of financial and demographical factors, before and after higher education, with a sample large enough to statistically isolate those factors that meaningfully impact a student’s post-graduation experiences in the labour market.

But there is a problem – in fact, two problems.

Canadians’ tax and census data is, of course, confidential. That’s why, if you want to work with more raw or granular data than what Statistics Canada provides on their website, you have to physically go to one of Statistics Canada’s Research Data Centers (RDCs), do your statistical analysis work there, and leave with only the anonymized results that you generated. Linking PIAAC and LISA data to these restricted files means researchers and policymakers can only analyze the linked data at an RDC.

Statistics Canada’s data also “sits” in very complex data files that require significant technical knowledge to access. Linking PIAAC and LISA data to Statistics Canada’s administrative data means researchers wishing to access the data must undergo a training process to learn how to work with the relevant files, and their associated variables, not to mention acquiring a strong understanding of Statistics Canada’s data collection methodology. Statistics Canada estimates a six-month learning process, which would be prohibitive for most researchers and policymakers wishing to make use of this potential fountain of information.

So researchers and policymakers are encountering a paradox: while the data they need is now more useful than ever, it is also more difficult than ever to access it.

Unlocking our skills data: The Research Initiative on Education and Skills

Luckily, these barriers are not insurmountable.

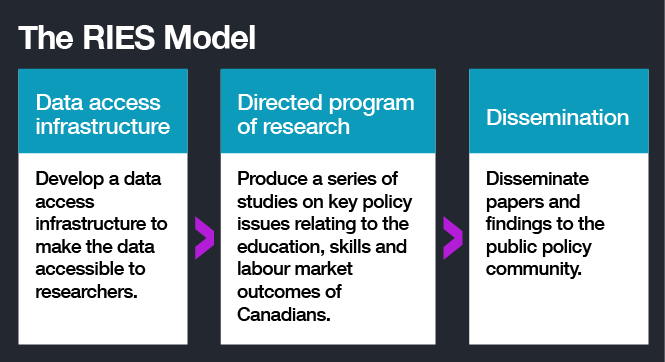

Under the new Research Initiative on Education and Skills (RIES), launched by the Mowat Centre and the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario (HEQCO), a team of well-trained researchers will work on the PIAAC and LISA data and its linkages to Statistics Canada’s administrative data. Working out of the Toronto RDC at the University of Toronto, they will produce their own research and collaborate with other interested researchers. This will mobilize the PIAAC-LISA data to help inform policy development in areas relating to education and skills.

Under this model, researchers outside of the Mowat Centre and HEQCO will be invited to collaborate on the initiative through a series of calls for papers. Paper authors will have access to the RIES research team, who can provide the specific data output needed to inform analyses. The policy research community will also be invited to participate in events meant to discuss and share research findings.

The RIES model has a number of advantages:

- Housing a centralized research team that is responsible for data production using the LISA-PIAAC surveys creates a hub of research expertise that mostly removes the steep learning curve for others to access and work with these datasets.

- By preserving and reusing data tools and methodology developed for individual research projects, the research team can greatly reduce the time needed to run analyses on subsequent projects.

- Because the research team directly analyzes the data to meet the needs of interested parties, this model opens the door to researchers and policymakers not heavily versed in statistical methodology to benefit from the PIAAC and LISA data, considerably broadening the reach of this unique collection of data.

Looking forward

In a knowledge-intensive economy, a country’s ability to sustain economic growth and enhance quality of life is driven by the skills of its workforce and citizens. Skills underpin employment, productivity, entrepreneurship and innovation in the economy. Skills also enable citizens to interact effectively together and with their public institutions to address an increasingly complex array of local, regional, national and global challenges.

At the same time, there is a risk that a knowledge-intensive economy could increase societal inequalities. A more equitable distribution of skills within the population, driven by equitable access to education and skills development, is the key to addressing economic inequality, gender inequality and inequality between ethnic and racial groups.

Accessing the linked PIAAC and LISA data is the key to better understanding how education, skills and labour market outcomes interact in Canada, and how to maximize their societal impact going forward.

Research Initiative on Education + Skills

The Research Initiative on Education and Skills is an innovative collaborative policy research initiative led by the Mowat Centre and the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. Its purpose is to access, analyze and mobilize data relating to the education, skills and labour market outcomes of Canadians, and to disseminate the findings to inform policy development.

MoreAuthor

Brad Seward

Release Date

June 4, 2018