June 18, 2015

One of the policy ideas getting more attention as the federal election approaches is the role of tax reform in generating revenue and correcting income inequality in Canada.

The 1966 Royal Commission on Taxation recommended tax rates not exceed 50 per cent due to “a psychological barrier to great effort, saving and profitable investment when the state can take more than half of potential gain.”

In the Canadian context, the main source for the idea of a 50 per cent psychological tax barrier seems to be the 1966 Royal Commission on Taxation (the Carter Commission). It recommended tax rates not exceed 50 per cent due to “a psychological barrier to great effort, saving and profitable investment when the state can take more than half of potential gain.”

More recent warnings against a 50 per cent tax rate have surfaced in the United Kingdom. The first was from a group of prominent economists and policy advisors in response to a tax rate increase from 40 to 50 per cent in 2011, which was subsequently reversed. The second was from a group of influential business leaders in 2014, which was challenged as a partisan move during the run-up to an election. Both groups voiced concerns about hampering economic growth and loss of domestic talent to “brain drain.”

What empirical evidence exists on this issue? There are “rough guesses” about human behaviour, but the actual evidence is unclear. We have learned a lot about the effect of marginal tax rate increases since 1966, but the lack of clear evidence for the psychological 50 per cent tax barrier raises an important question: should this particular threshold be a real concern for policy-makers? Or does it create an anchoring bias in decision-making based upon an arbitrary value?

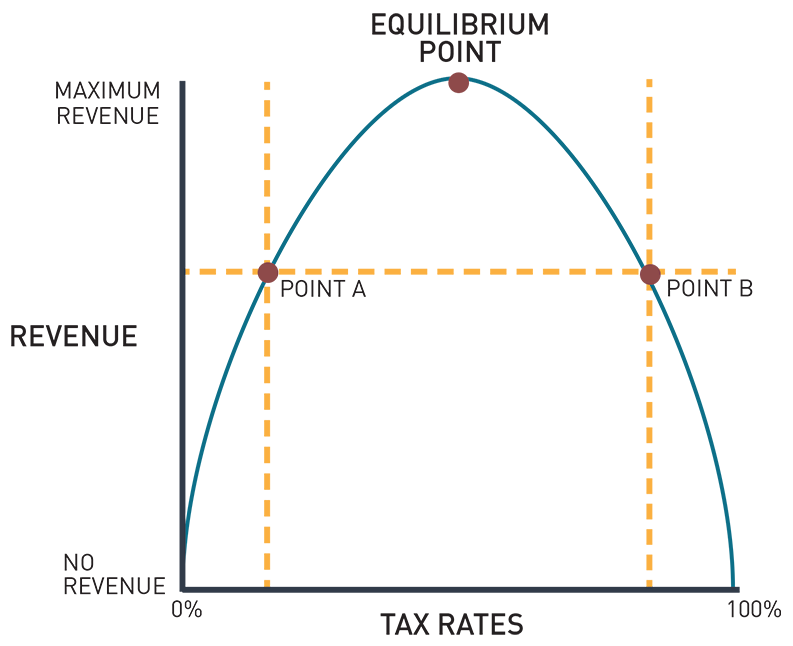

In the abstract, economic theory can support the claim for an upper tax threshold. The Laffer Curve, a graphical representation of hypothetical tax rates and resulting government revenues, is the best known example. Arthur Laffer’s theory argues that at the most extreme rates of 0 and 100 per cent, no government can raise revenue – at a rate of zero, the government is not demanding any revenue, and at a rate of 100 per cent no one will bother earning income. Somewhere between the two extremes is a sweet spot where government revenue is maximized. However, the exact shape of the curve is disputed and an ideal tax rate has never been identified. This is because the peak of the Laffer curve (i.e., the sweet spot) changes drastically given small modifications to values, and it is not clear what the correct values should be.

Hauser’s Law (named for Kurt Hauser in the 1990s) revealed that while marginal tax rates have fluctuated widely in the United States since World War II, the resulting revenues as a portion of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) have remained relatively constant. This also implies that there is some maximum amount of taxation that a population will tolerate before widespread avoidance or sheltering occurs. However, both concepts suggest that the exact threshold depends on a taxpayer’s measured responsiveness to such a change (i.e. their elasticity of taxable income).

Outside of economic theory, empirical evidence for the 50 per cent barrier is limited. One interesting case study is explored in a report by the UK’s Revenue and Customs Authority, which examined 2010-2011 self-assessment returns that followed the above mentioned tax rate increase from 40 to 50 per cent. The study found that an estimated £16 to £18 million of income was brought forward to avoid the pending tax change. Though this situation appears to provide compelling proof of tax-minimizing behaviour, it only represents short-term reactions as the increase was quickly reversed. No one knows whether this income-shifting would have continued through the following years, or if increased rates would have generated additional government revenue in the long-term. This would not be easy to estimate either, since economists point out that calculating a taxpayer’s responsiveness to change over the long-run is challenging and hardly convincing.

Some provinces such as Quebec and New Brunswick already nearly touch or exceed 50 per cent in their highest federal/provincial income tax brackets.

Governments should always be cautious when considering tax reform and must consider all potential behavioural responses. Public debate about income tax structures has historically been quite politicized, but it is crucial to look beyond the politics and understand what governments should really be worried about when it comes to taxation levels. The evidence for a bona fide barrier at the 50 per cent threshold is murky.

It is important to remember that when analyzing policy, context matters and every country faces a different set of circumstances. In fact, some provinces such as Quebec and New Brunswick already nearly touch or exceed 50 per cent in their highest federal/provincial income tax brackets. Closer study on the issue would be instructive, especially in examining jurisdictions just before and after tax rates cross the 50 per cent mark. As unsatisfying as it may be, it is difficult to determine whether changes that put other jurisdictions over the 50 per cent rate would generate more government revenue or simply result in increased tax-minimizing behaviour.

More related to this topic

Author

Jordann Thirgood

Release Date

June 18, 2015