June 27, 2017

A portable benefits scheme for all Canadian workers

Imagine it’s the year 2067.

Fifty years from now, what it means to work and have a career has changed entirely and Canada’s labour market is nearly unrecognizable. Innovation and investment have left the economy booming and labour productivity has hit a record high, but almost no one works in the once-standard nine-to-five form of employment.

The above scenario would sound like a dystopia of precarious employment and economic vulnerability in 2017. Fortunately, by 2067, governments will have responded to the changing nature of work with adequate social supports. In this new economy, all workers have access to the same benefits, rights and protections, regardless of employer. No one is disadvantaged by their employee classification or the nature of their work. Every working Canadian receives paid leave; prescription drug, vision and dental coverage; opportunities for lifelong learning; robust public pensions and adequate supplemental income should they fall out of work. These benefits can all be accessed from their Portable Benefits Account (PBA) – a personalized social safety net that you take from job to job, contract to contract, task to task.

In the years following World War II, the bulk of working Canadians were male, employed in the trades or manufacturing sectors and engaged in a Standard Employment Relationship with their employer. This relationship implied a significant degree of security: the job was full-time, permanent and paid well enough to support a family on a single income. The employer provided benefits to cover unexpected expenses for the individual and often their family, including prescription drug, vision and dental coverage as well as life and disability insurance. The employer helped facilitate adequate savings for future retirement. A worker often received sufficient training, opportunities for advancement and likely remained employed by that organization for most of his (or sometimes her) working life. Furthermore, labour unions held employers to account in pursuit of decent wages, reasonable work hours and fair treatment of all employees.

Canada built its social architecture around this reality in the 1940s, 50s and 60s. Policies and programs like Medicare and Unemployment Insurance operated on the assumption that workers had a strong relationship with their employer and their union. The role of government was to fill the relatively few gaps in this system, such as temporary income assistance during spells of unemployment. This suite of supports worked well for Canadians over the years, and aside from some relatively minor tweaks, remains largely unchanged to this day.

Yet it is clear that significant changes to the status quo are needed to meet the demands of the new labour market facing Canadian workers, and to provide the supports Canadians will need in the decades to come.

The Standard Employment Relationship is becoming increasingly uncommon as jobs that were once characterized by stable, full-time career paths are unbundled into part-time jobs, temporary contracts, tasks and gigs. Between October 2015 and October 2016, almost 90 per cent of new jobs created in Canada were part-time. The proportion of the workforce employed in temporary positions has increased by 57 per cent since the late 1990s. Technology platforms continue to come online and classify their workers as independent contractors rather than employees. These trends seem destined to continue and in rapid fashion: for instance, estimates in the US indicate that 40 per cent of the workforce could be freelancers by 2020.

Each and every Canadian worker – regardless of their employee classification or the nature of their work – should have access to the same benefits, protections and opportunities.

The role of employers in providing important benefits and protections is diminishing across a range of industries. As a result, gaping holes have emerged in the social safety net. Workers who are employed on a temporary or part-time basis rarely qualify for employment insurance (EI) when they fall out of work, and independent contractors are unable to avail themselves of the legal rights and protections available to employees. Workers without benefits are left to pay out of pocket for prescription drugs. Their stagnant wages are quickly consumed by soaring costs for shelter and child care. Employers are investing less in their workers, and opportunities for education, training and skills development seem increasingly out of reach for many Canadian workers.

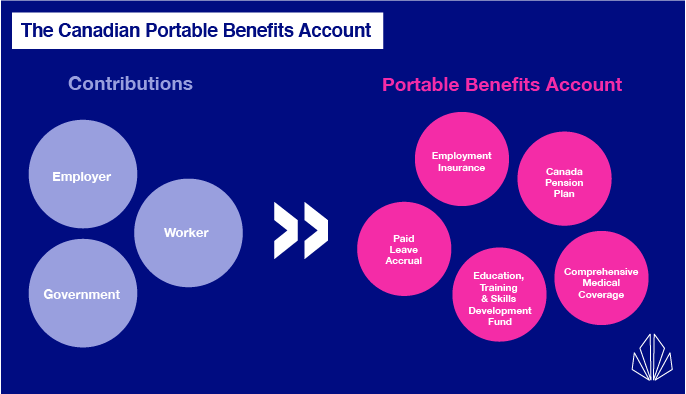

To ensure adequate support for the workforce of the future, all Canadian workers – regardless of employee classification – should have access to a Portable Benefits Account (PBA). This mechanism would consist of a suite of benefits similar to those provided by employers of the past, but would come from various contribution sources and be carried between jobs. It would provide workers with a degree of stability and security that is independent from both their relationship with their employers, and the nature of their work.

How could it work in Canada?

It has been suggested that federal administration of such a program would result in the most consistent and workable response, although in Canada this would also require significant cooperation and buy-in from the provinces and territories. Contributions would be made from all relevant parties: the worker, the employer and government. These contributions would be pro-rated to the number of hours worked by an individual, or for those working on a task basis, a percentage of gross wages. Part-time workers would thus be eligible for a portion of the same benefits as a full-time worker. This eliminates any perverse incentives of employers shifting towards part-time or task-based work in order to avoid the provision of benefits to which full-time workers are entitled.

The PBA would be mandatory for all workers and employers, so that all employers would be required to make pro-rated contributions for the hours put into their organization, from both employees and independent contractors. This would render the currently troublesome distinction between the two classifications irrelevant.

The infrastructure for the PBA would extend from existing mechanisms at the federal level, building upon the way in which Employment Insurance (EI) and Canadian Pension Plan (CPP) contributions are collected. Contributions would be deducted from an individual’s pay and matched by his or her employer as well as government. These contributions would then be directed into each component of the PBA, including existing safety net programs such as EI and CPP. Additional elements should be determined by an analysis of current protections and existing gaps.

In Canada, the following components should be viewed as most vital:

Paid leave, including both sick days and vacation time

For Canadians who are employed on a part-time or temporary basis, paid leave is typically unavailable. While a percentage of wages may be paid out in the form of vacation pay in some jurisdictions, time away from the job must be taken without pay. Should a precarious worker fall seriously ill or face some other unforeseen circumstance, they are not entitled to paid leave in the same manner as a full-time employee.

A PBA could incorporate a formula similar to that of a municipal sick leave ordinance recently legislated in Los Angeles. Employers can choose to provide either 48 hours to an employee at the beginning of each year of employment, calendar year, or 12-month period; or provide one hour of paid sick leave per every 30 hours worked, capped at 72 hours.

Canada’s PBA should allow workers to claim their sick hours at any point of the year for medical reasons (including mental health and well-being), to care for a family member, or for other unexpected circumstances. Individuals should also have the opportunity to separately accrue vacation time in a similar manner.

Prescription drug coverage, as well as vision and dental coverage

Canada remains the only industrialized nation that provides universal public health care without providing universal public drug coverage. While many employees had access to private plans through their workplace in the past, around one-third of working Canadians do not have any access to employer-provided health benefits today. This number is significantly higher for women, part-time workers, and those under the age of 25. Canadians are left to pay out of pocket and many simply neglect to fill a prescription as a result.

Canada should consider San Francisco’s medical reimbursement account (MRA) as an example model for this component of the PBA. Prior to the introduction of Obamacare, the local government introduced the MRA as a mechanism to extend coverage to all residents for various expenses such as medical visits, vision, dental and prescription drugs. Much like the MRA, a Canadian PBA should extend coverage to all workers, regardless of employee classification.

Education, training and skills development fund

Investment in Canadian workers by both government and employers is at record lows. Providing the opportunity for lifelong learning will be crucial to prepare our workforce for the future. This should include upskilling, re-training and educational courses made available and accessible to Canadians beyond the years of traditional schooling.

A portion of PBA contributions should be allocated for workforce development on an individual basis, similar to a recent initiative in Singapore. SkillsFuture provides all individuals 25 years of age and older with an initial credit of $500 to use on a range of government-supported courses, which are regularly topped up and never expire. The French federal government has recently rolled out Personal Activity Accounts with a similar mission. In Canada, this component could provide an important tool to promote lifelong learning, and should coexist with other targeted programs for vulnerable workers.

Of course, the precise makeup of a PBA could be infinitely varied. There are a number of other crucial social supports that could be incorporated, such as life insurance, disability or chronic illness insurance and even a housing benefit.

Contributions would flow from all work that an individual participates in and be pooled into a single account. This means that a full-time salaried employee engaged in Standard Employment Relationship and an independent contractor cobbling together tasks to reach 40 hours a week are entitled to the exact same benefits, protections and opportunities.

The strongest rationale for introducing a PBA is that it would provide stability without detracting from the flexibility of the new economy. For corporations, particularly technology platforms under fire for precarious work practices, it would be an alternative to facing mounting class-action lawsuits. For governments, it would strike a balance between supporting and protecting workers, while also encouraging economic growth and addressing long-term economic concerns of an aging population and rising healthcare costs. Ultimately, a PBA acts as an automatic stabilizer – providing stimulus to maintain consumer spending and encouraging innovation in a way that doesn’t disadvantage workers.

Critics will certainly say this approach is prohibitively expensive and burdensome, especially if government contributions were financed in part by an increase in the sales tax, as has been suggested. But other revenue-generating schemes could be utilized that put less burden on workers who are already contributing to the PBA directly. For example, the government could pursue a reformed corporate rent tax that applies to above-normal profits as a means of funding the PBA.

The costs of inaction are far too high. When people do not have access to adequate supports and fall through the cracks, strain is put on the system in other high-cost ways, such as recurrent hospital stays. There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that public coverage of such programs results in economic advantages over the long run. Indeed, prescription drug coverage can result in billions in cost savings for both patients and governments, while accessible education and training means more skilled workers are entering the workforce and contributing to economic growth.

It goes without saying that a PBA, while transformational, would not be sufficient in the absence of adequate employment standards, fair wages and decent work practices. It would not take employers off the hook for ensuring safe and welcoming work environments. It also assumes the economy of the future still requires an adequate amount of human labour. But this mechanism does provide the necessary baseline to protect workers and prepare them for the labour market of the future – one that is likely to be characterized by frequent, rapid and widespread changes.

As we recognize Canada’s 150th birthday, it’s important to look back and take stock of how far we’ve come, as well as to look forward and prepare for the changes on the way. Above all, it’s a time to celebrate Canadians and the hard work that they do. For Canada’s sesquicentennial, policymakers should carefully consider portable benefits as means of providing security for all. Doing so could transform the way we think about work, ready our nation’s workforce for disruption and provide the stability necessary for Canadians to build prosperous lives.

As Canada marks its 150th birthday this year, Canadians have a historic opportunity not only to celebrate a century and a half of accomplishments, but also to look forward to what we can achieve in the future. The Mowat Centre is releasing a series of short written pieces and video interviews that look ahead and present a variety of bold, potentially transformative policy ideas.

More Bold IdeasAuthor

Jordann Thirgood