March 7, 2019

The federal government will issue its 2019 budget on March 19th. As always, the majority of federal spending will come in the form of transfer payments to Canada’s provinces and citizens. And the question of the fairness of these transfers is bound to arise.

What makes for fair transfers?

In order to be fair, reallocation must be justified by principles, and the mechanism for redistribution should be fit-for-purpose. Approaches to reallocation that define need on a basis other than population should use measures that are transparent, well established and justifiable. Deviations from well-established principles should be rare, explained transparently and subject to open debate.

To meet this threshold a transfer needs to pass a threefold test:

- Adequate

Is the federal government transferring enough to meet its obligations? - Non-conditional

Is the federal government avoiding the imposition of overly rigid conditions or the undue leveraging of funding from provinces?1 - Principled

Is federal funding allocated in a clear and principled manner?

The path towards a more principled and fair transfers system is both clear and achievable.

Canada’s unprincipled allocations

In recent work, we’ve analyzed whether Canada’s transfers are indeed allocated in a principled manner, quantifying how much unprincipled allocations are costing Ontarians. While we focus on Ontario, our methodology can be used to assess the impact of unprincipled allocations in other provinces that pay more into Canada’s transfers than they receive back in transfer payments.

In general, there are a number of guiding principles that should be used to determine the appropriate approach for allocating federal transfer payments:

- Clear and transparent

- Fair to Canadians regardless of where they live

- Consistent with the policy objectives of the transfer

- Predictable, with the flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances

Depending on circumstances, allocations consistent with these principles can take a variety of forms:

- Per-capita – allocates transfers according to share of population

- Per client – distributes transfers based on a province’s share of the population that would be targeted for assistance by the program

- Need-based – accounts for the demand for, and different cost of, providing comparable services

- Merit-based – funding awarded to projects that meet objective and transparent criteria

Our analysis found that some of Canada’s transfers are indeed allocated in a principled manner. The Canada Health Transfer (CHT) and Canada Social Transfer (CST), for example, are provided on a per-capita basis, with each province receiving transfers equal to its share of the country’s population. This means that governments receive necessary funds to provide public services to their residents. Similarly, Old-Age Security (OAS) and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) are income-tested, meaning that recipients of funding are those who need it most, therefore meeting the intended goal of the program.

But too many of Canada’s transfers are not allocated in a principled manner. How much do these unprincipled allocations cost Ontarians? Here are the numbers:

Equalization, Employment Insurance & labour market transfers

These are the three most prominent federal transfers currently distributed on an unprincipled basis. The constitutionally-mandated Equalization program is meant to enable provinces to provide reasonably comparable services at reasonably comparable tax rates, currently done by transferring federal funds to provinces with lower “revenue-raising capacity.” However, it does not recognize the higher cost of delivering services in Ontario.

Employment Insurance collects money from workers and employers in all provinces in order to provide assistance for Canadians temporarily out of work. Labour market transfers are allocated from EI premiums and general revenues to assist unemployed and under-employed Canadians by providing them with training, skills development and job search services. Both of these programs would be far more principled if their allocations more closely matched Ontario’s 36.1 per cent share of Canada’s unemployed population in 2017.

The gap between Ontario’s share of actual Equalization, Employment Insurance, and labour market transfers, and the share it would have under a principled allocation, 2017-18 ($ millions)

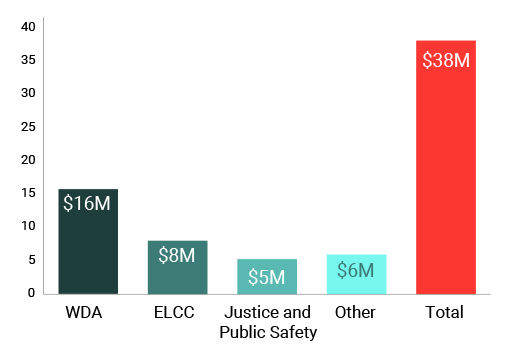

Minor transfers to provinces and territories

This category includes a host of smaller transfers to provincial governments, such as Workforce Development Agreements (WDAs), support for early learning and child care (ELCC), transfers in the areas of justice and public safety, and others.

The gap between Ontario’s share of actual minor transfers and the share it would have under a principled allocation, 2017-18 ($ millions)

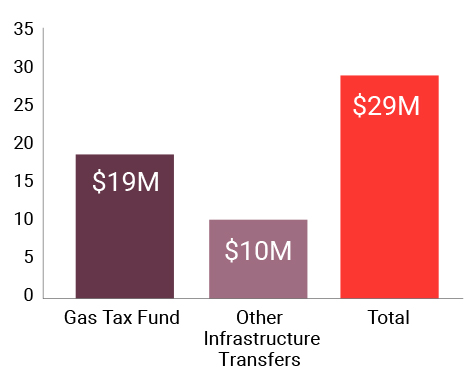

Infrastructure transfers

This category includes transfers from general revenues to provinces and municipalities to fund infrastructure needs.

The gap between Ontario’s share of actual infrastructure transfers and the share it would have under a principled allocation, 2017-18 ($ millions)

Transfers to support innovation, science & economic development

These are multiple transfers from general revenues distributed directly to companies and research institutions by a number of federal departments, regional development agencies and research granting agencies.

The gap between Ontario’s share of actual economic development and research transfers and the share it would have under a principled allocation, 2017-18 ($ millions)

Transfers to Indigenous governments and organizations

Transfers from general revenues to Indigenous governments and organizations, in a variety of areas such as health, education and training, infrastructure, justice, and administration, as well as transfers to negotiate, support and implement comprehensive land claims and self-government.

The gap between Ontario’s share of actual transfers to Indigenous governments and organizations and the share it would have under a principled allocation, 2017-18 ($ millions)

The Path Forward

The path towards a more principled and fair transfers system is both clear and achievable. As a first step, the federal government should transparently account for its choice of allocation method. Where deviations from a principles-based allocation exist, these should be justified. Over time, these deviations from principle should be addressed.

At the same time, the federal government should ensure that transfers are adequate to meet federal obligations and that they do not impose overly rigid conditions or unduly leverage funding from provinces. Adequacy and conditionality mean that the gap faced by Ontarians is in fact much higher than indicated above. Addressing this will ensure that federal funding is allocated in the fairest way possible.

- In the past, conditionality has served to prevent the most promising or highest-priority projects from being eligible for federal funding simply because provinces had already vetted and provided partial funding for them. It has also served to force provinces to divert funding to federal priorities from projects they deemed to be more needed in the province. [↩]