March 22, 2019

Findings from the Environics Institute point to rising political alienation in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Atlantic Canada – resentment that Ottawa ignores at its own peril, researchers warn

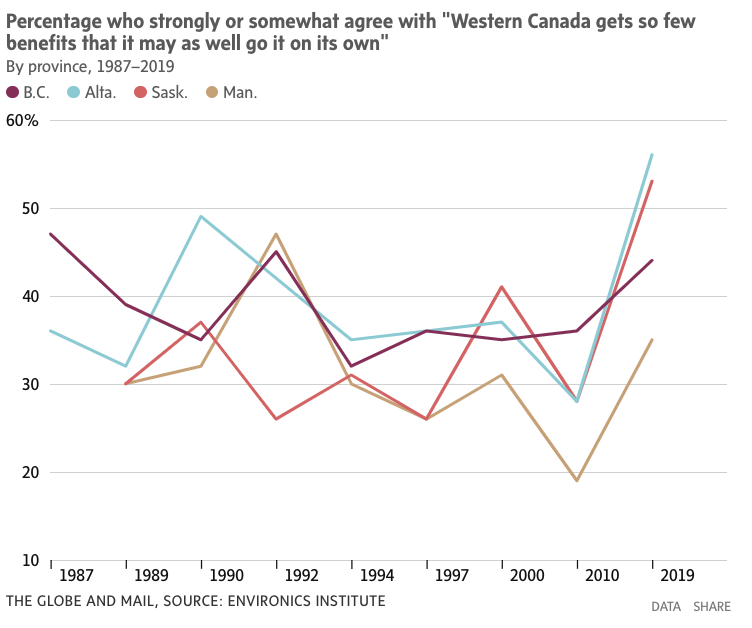

Western Canada is experiencing a rising tide of resentment toward the rest of the country amidst political battles over pipelines, emissions and equalization payments, with a majority in Alberta and Saskatchewan now saying they get so little out of Confederation that they might as well leave.

That’s according to a massive new survey from the Environics Institute, which confirms a widespread impression that Western alienation has gotten worse since Justin Trudeau became Prime Minister. Add a persistent malaise in Atlantic Canada, and the survey depicts an uneasy Confederation on the heels of its 150th anniversary.

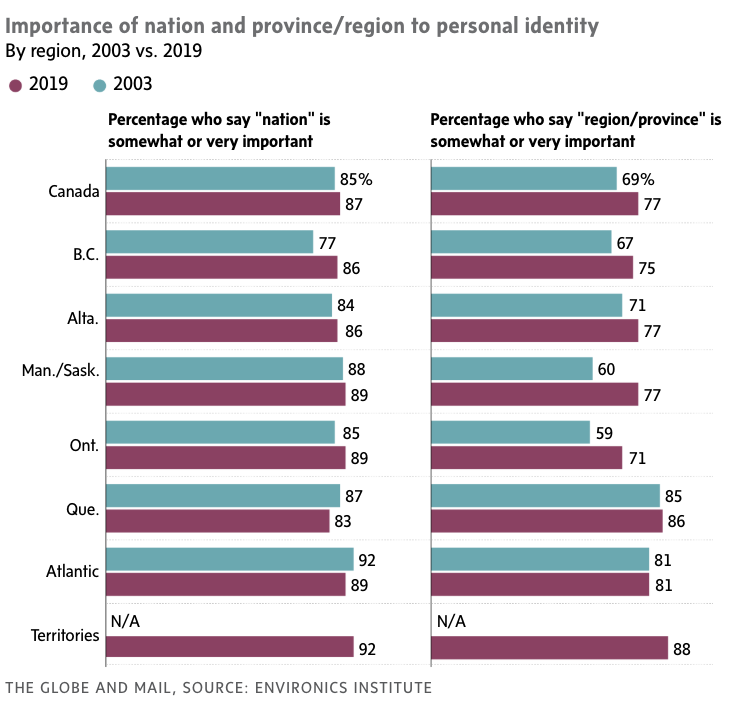

The poll, which asked more than 5,000 people about their attitudes toward the country between December and January, found a federation feeling more provincial. The proportion of Canadians who said their province or region is important to their sense of self rose from 69 per cent to 77 per cent in the past decade and a half, even as talk of Quebec separatism has cooled.

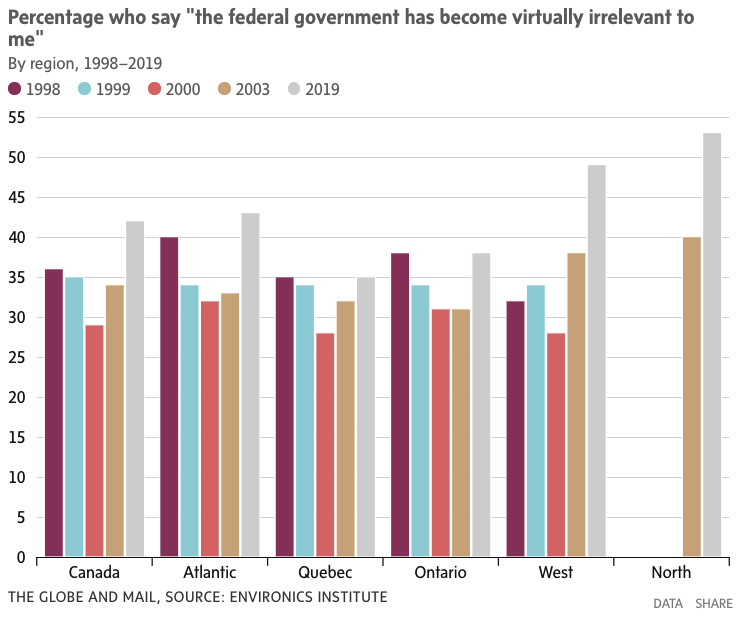

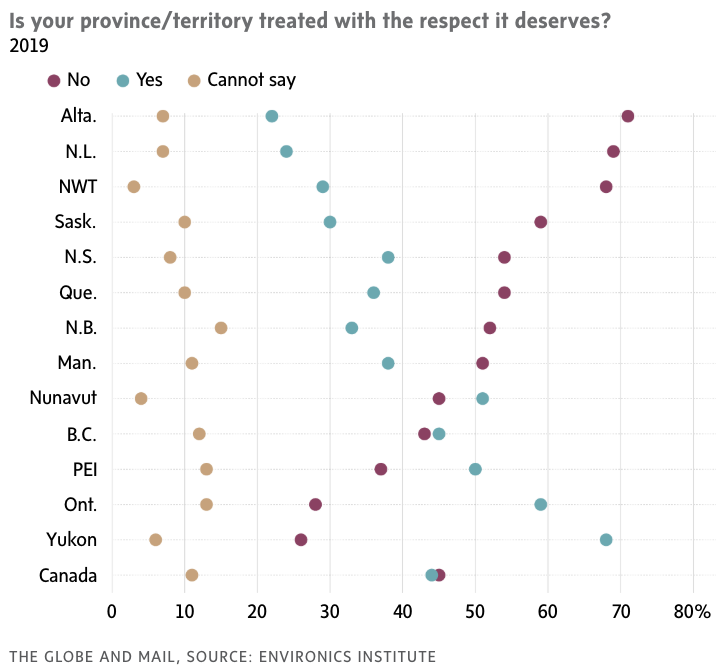

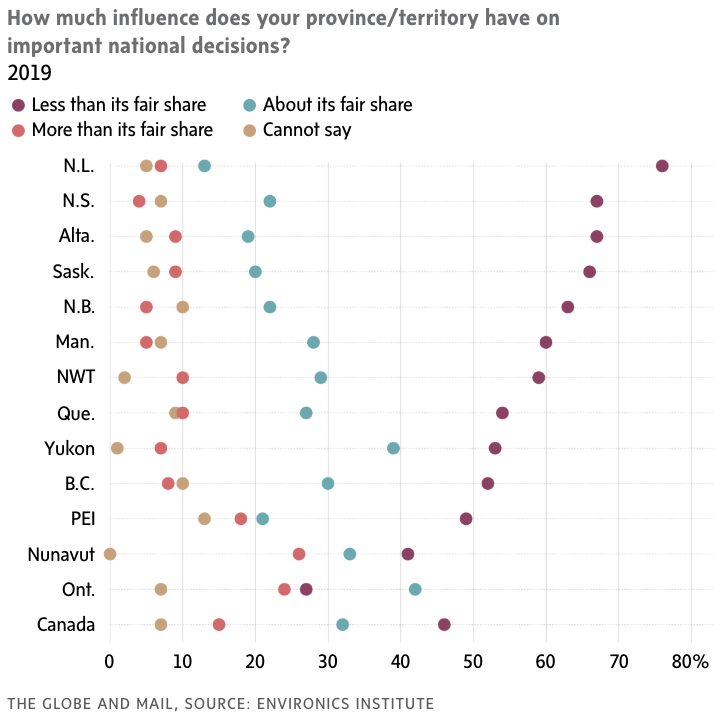

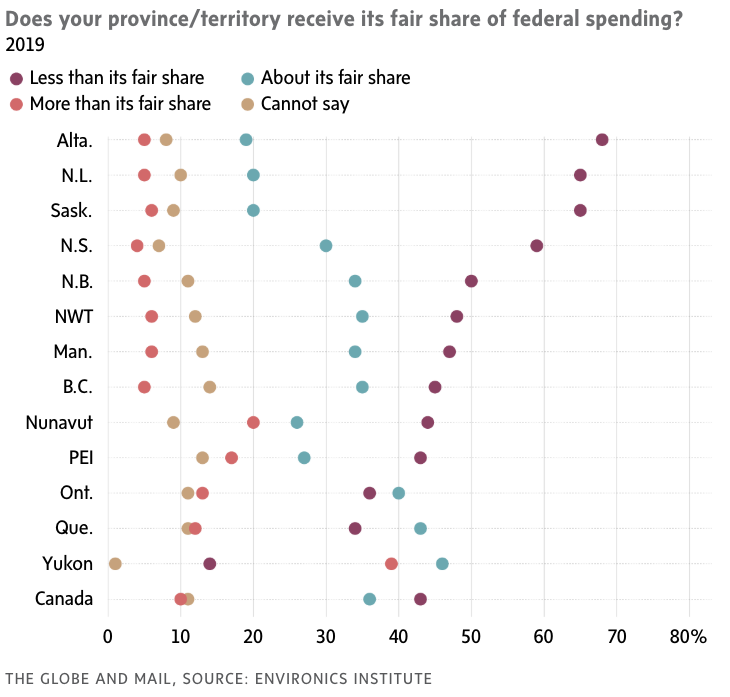

That change has been paired with a growing sense of disillusionment with the country’s federal arrangements in the East and West alike. The Canadians most likely to feel they lack a fair share of influence over how the country is run live in Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Saskatchewan and Alberta.

The findings should serve as a wake-up call to Ottawa’s political elite and spur reforms that decentralize power, said Donald Savoie, the Canada Research Chair in Public Administration and Governance at the University of Moncton.

“What you’re seeing in Western Canada and Atlantic Canada – it’s the start,” he said. “I don’t think people in the Ottawa bubble get it. But it’s going to bite.”

Recent causes of provincial pique, from the carbon tax to charges of Quebec favouritism in the SNC-Lavalin affair, have grabbed headlines lately. But Mr. Savoie sees structural forces behind the trend. The political dominance and relative contentment of central Canada have been entrenched in part thanks to the toothlessness of the Senate, he said – the Red Chamber could provide a counterweight to the dominance of populous provinces in the House of Commons if it had more clout, similar to the role the U.S. Senate plays.

“You win power in Canada by winning Ontario and you win a majority by winning Quebec. It’s that simple,” he said. “We have national institutions that are incapable of looking at the regional factor.”

Indeed, at least 50 per cent of every Atlantic province but Prince Edward Island now feels their province lacks its fair share of federal funding and doesn’t get the respect it deserves. Such sentiments are hardly new in the region. Eastern Canada has gone through long periods of feeling like the junior siblings of Confederation, locked out of big decisions and paid little heed by the power brokers of Montreal, Ottawa and Toronto. In 1867, Nova Scotia’s parliamentary delegation featured 18 members opposed to Confederation and only one in favour. Newfoundland, of course, didn’t enter Canada until 1949.

That ambivalence toward the rest of the country has been heightened at times by a sense of neglect, Mr. Savoie said, made manifest by the location of Crown corporations in Ontario and Quebec and the growing concentration of federal bureaucrats in the National Capital Region.

Western rage at the “Laurentian elite” is hardly new, either. It flared up most famously as a result of Pierre Trudeau’s National Energy Program in the early 1980s.

But the stubbornness of provincial discontent shouldn’t take away from the serious escalation of ill feeling in Alberta and Saskatchewan that this polling reveals, said Andrew Parkin, director of the Mowat Centre, an Ontario think tank that helped produce the survey along with a handful of other research organizations. (The group used questions that have been asked in national surveys dating back to the 1980s to track opinion over time.)

“There’s a risk there of going, ‘The provinces always want more money, always want more power, and this is just complaining,’ ” he said. “Yes, but it is accentuated at certain places and certain times.”

Now is one of those times.

The federal government’s inability to win approval for major pipelines and its law taxing carbon emissions during a downturn in the domestic oil industry appear to have angered Saskatchewan and Alberta more than at any time in over a generation.

Fifty-seven per cent of residents in both provinces now say the federal government has become personally irrelevant to them. And for the first time since pollsters have been asking the question – as far back as 1987 – majorities in Alberta and Saskatchewan now agree with the statement, “Western Canada gets so few benefits from being part of Canada that they might as well go it on their own.”

“Every survey that’s ever been done about federalism has had most of the provinces outside of Ontario express some measure of discontent,” Mr. Parkin said. Still, “to not notice that alienation is higher than when Preston Manning first came on the scene, and to miss that concern about the future of the French language is stronger in Quebec than when Lucien Bouchard was premier, is to risk missing something fundamental about how the country is working.”

Nowhere is the national angst about Confederation more acute than in Alberta, where fully 71 per cent of residents feel their province doesn’t get the respect it deserves. That is partly due to a sputtering oil sector and anemic economy that have produced high unemployment and swelling public debt, said Colleen Collins, vice-president of the Canada West Foundation, which collaborated on the study.

But the anger also draws on more emotional, symbolic sources. Ms. Collins pointed to remarks by Quebec Premier François Legault dismissing the prospect of a pipeline carrying Alberta’s “dirty energy” through his province, which riled many in the oil patch.

“For one of our own to say, ‘We don’t want your dirty oil’ – that really hurts,” she said. “That felt like a kick in the gut.

“We know we’re blessed and we’re more than happy to share, but it comes down to that question of respect.”

State of the federation: Key takeaways from the survey

Publication

The Globe & Mail

Author

Eric Andrew-Gee

Release Date

March 22, 2019