December 5, 2016

Provincial and Territorial Premiers have called on the Prime Minister for a meeting dedicated to the issue of health care funding. The call comes against the backdrop of federal plans to decrease the growth rate of federal health transfers to the provinces. Without federal action, the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) funding escalator will fall to the 3 per cent floor currently set out in federal legislation starting next year.

Developments such as these have led some to argue that the federal government should do less on the health care funding front. Their argument goes something like this: Federal funding removes the incentive for provinces to control spending and undertake structural reform to improve health system effectiveness.

Quite frankly, this line of argument ignores the overall low level of support the federal government actually provides for provincial-territorial spending on health care. Federal cash support for provincial health care spending through the CHT stood at 23.5 per cent in 2015-16. The idea that provinces – already shouldering the burden for 76.5 per cent of health spending – don’t already have a huge incentive to control costs is absurd.

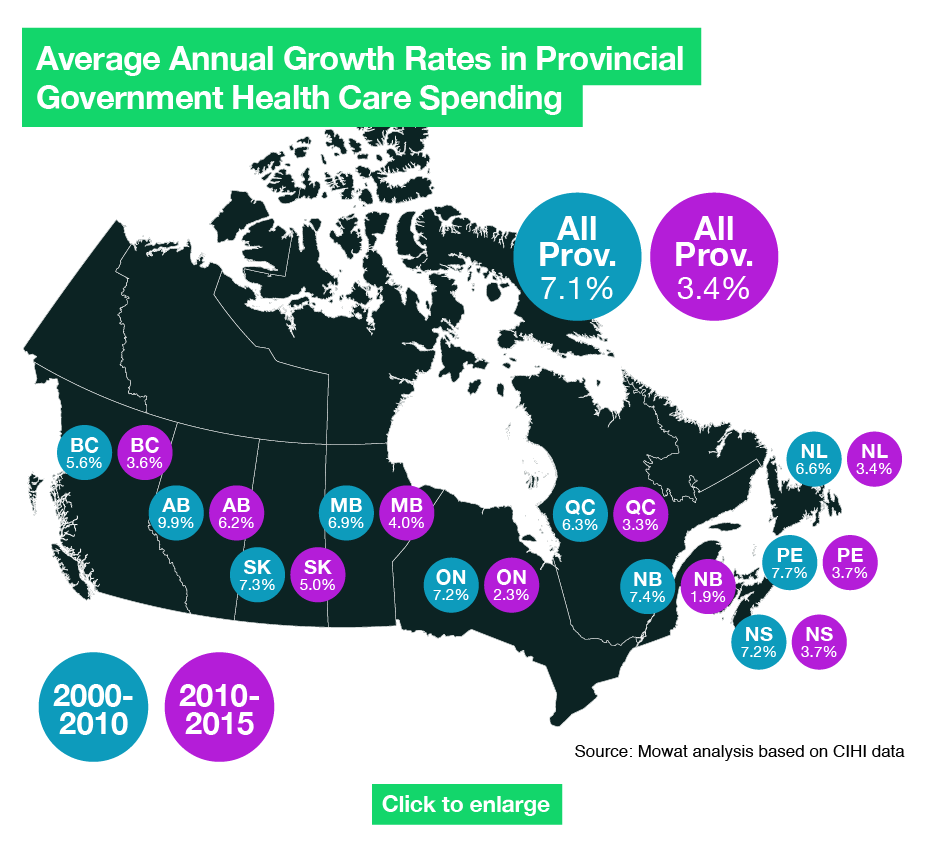

In fact, provinces have done a good job containing costs in recent years. What had been described as runaway costs by some were substantially reined in. Compared to the 7.1 per cent average annual growth in health care spending between 2000-01 and 2009-10, provinces have halved those growth rates since. Between 2009-10 and 2014-15, annual growth rates have averaged as low as 2.3 per cent in Ontario or 1.9 per cent in New Brunswick. These rates of growth are not the result of the federal government somehow providing provinces with the “right” incentives to constrain costs. They reflect the fiscal realities caused by the slow economic recovery since 2008, and the need for provinces to continually seek health care efficiencies to allow them to reinvest in other priorities like infrastructure and poverty reduction.

In the coming years, however, provincial health care systems are projected to groan under the weight of an aging population. The first of the baby-boomers (born in 1946) turned 70 this year. In ten years, they will turn 80. Seniors on average account for a larger share of the health budget, so as the large cohort of baby-boomers age, there will be a larger share of the population consuming a larger share of the health budget. To prevent this scenario from wreaking havoc on provincial balance sheets, transformative change is needed. Provinces are generally doing what they can with limited resources available in the current fiscal environment, but the change required to meet the challenges that an aging population will bring to the health care system will be a large-scale endeavour.

The need to transform the health sector is a historic opportunity for the federal government to re-establish its role as a full partner in the health care system. A partnership between provinces and the federal government whereby each shared the costs of running the system (more-or-less) equally between them was how Canada’s health care system was designed.

Currently, provincial health care systems funnel too many chronic cases through the acute care system. This is an expensive and inefficient care delivery model. The problem is: where do you go if all that exist are emergency rooms and other acute care facilities? Keeping non-acute cases out of acute care settings must be the over-arching priority for transformation in the health sector. Canada needs a robust, patient-centred community care system to complement and take pressure off the acute care system. Building that system will take both time and money, and the federal government is needed now more than ever.

The need to transform the health sector is a historic opportunity for the federal government to re-establish its role as a full partner in the health care system. A partnership between provinces and the federal government whereby each shared the costs of running the system (more-or-less) equally between them was how Canada’s health care system was designed. At least, that was the idea fifty years ago when Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson and the provinces agreed to extend universal access to medicare. If the federal government were to once again fund health care like a partnership between equals, it would have to add $10 billion to the Canada Health Transfer envelope it currently disburses annually.

For their part, provinces must commit to using new federal health funding to buy transformation. The federal government will want assurances that the money is in fact being used for those purposes.

The tool the federal government generally uses to secure those assurances comes in the form of hard conditions on transfers. This is precisely the same tool that tends cause consternation in provincial capitals – to varying degrees – about intrusion into provincial jurisdiction. This is understandable in the Canadian context, where hard conditions have shown to lead to misdirection of spending to areas that are not necessarily shared priorities. Provincial consternation is amplified by past examples of unilateral federal abandonment of what were supposed to be shared priorities between orders of government. There needs to be more trust on both sides to secure a sustainable partnership in health care for Canadians.

There are ways to mitigate the provinces’ anxieties around “creeping conditionality” while securing the transparency and accountability around spending that the federal government seeks. The answer lies in effective, transparent institutions. Canada needs a truly pan-Canadian (not federal) institution mandated to promote transparency and accountability in health care. Such an institution should report on how wisely health care dollars are being spent by providing evidence-based assessments and recommendations. In addition, it should be relied upon to furnish intergovernmental discussions with impartial facts.

Transparency, facts and a renewal of true partnership are all key components to re-establishing trust in an area too often tinged by intergovernmental tensions. Trust between provinces and the federal government will be instrumental in fostering the collaboration required to address the actual challenges facing the health sector. To confront these challenges, more will be required out of the federal government, not less.

More related to this topic

Authors

Erich Hartmann

Release Date

Dec 5, 2016