January 10, 2018

The controversy stemming from the decision of Ontario senator Lynn Beyak to publish comments she received from the public about the residential school system – comments that her own party leader called “racist” – has raised some uncomfortable questions about the attitudes of Canadians towards Indigenous peoples and the issue of reconciliation.

The Mowat Centre’s survey was conducted in November 2017, two and a half years after the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada’s 94 calls to action.2 These calls certainly prompted a government response. Ottawa, for instance, announced it would support the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and formed a new ministry of Crown-Indigenous Relations. The Ontario government issued a Reconciliation Action Plan with a three-year commitment of $250 million for programs and actions focused on reconciliation. It also changed the name of the provincial Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs to the Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation “to demonstrate Ontario’s long-term commitment and efforts toward reconciliation.”3

But are citizens as seized with the issue as Canada’s governments?

The survey confirms that there is strong support among the public for Indigenous communities and recognition of the obstacles they face. For instance, seven in ten Ontarians agree that it is beneficial to all Canadians that the distinctive cultures of Indigenous peoples remain strong, while two-thirds acknowledge that the situation of Indigenous peoples in Canada is worse than that of other Canadians.

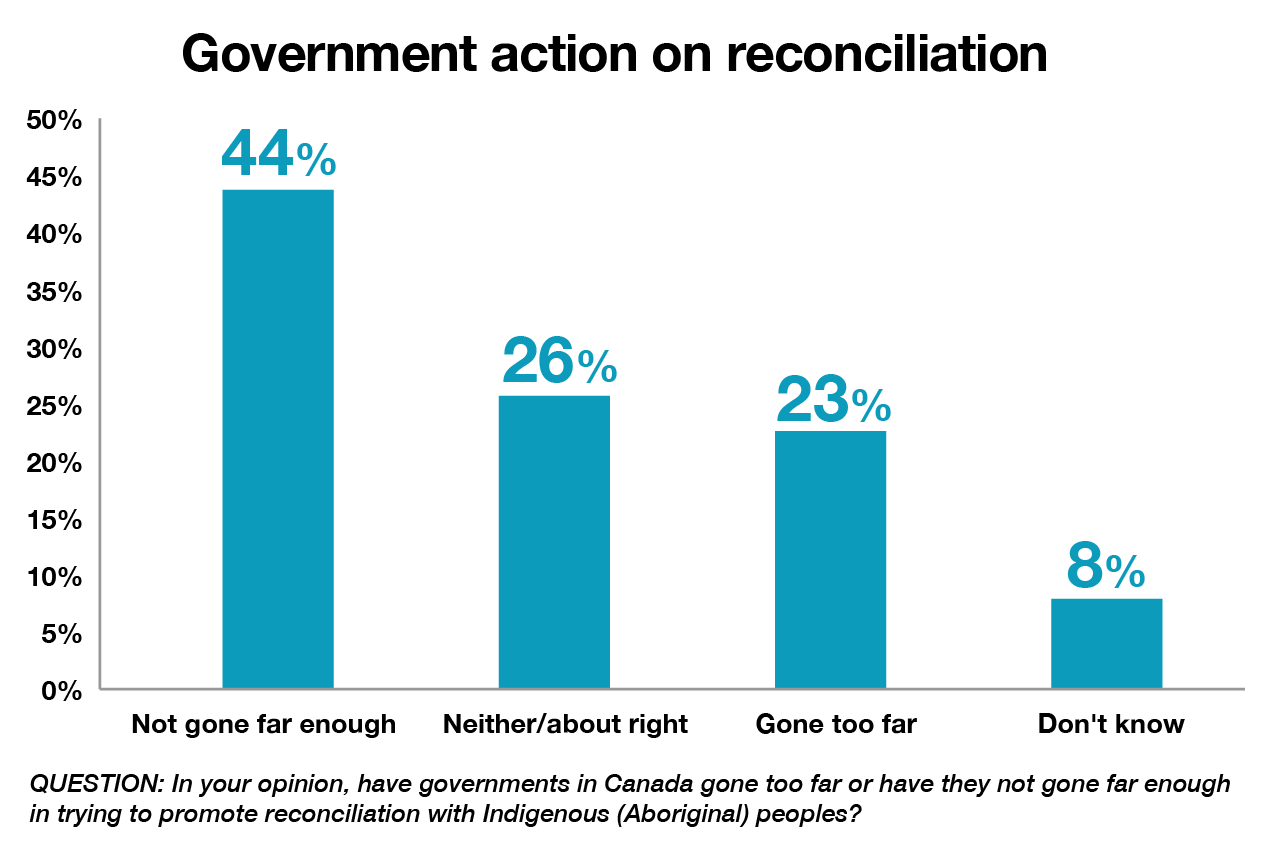

Most Ontarians also appear to accept the need for government action on reconciliation. Seven in ten say governments in Canada either are doing about enough or have not gone far enough in trying to promote reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

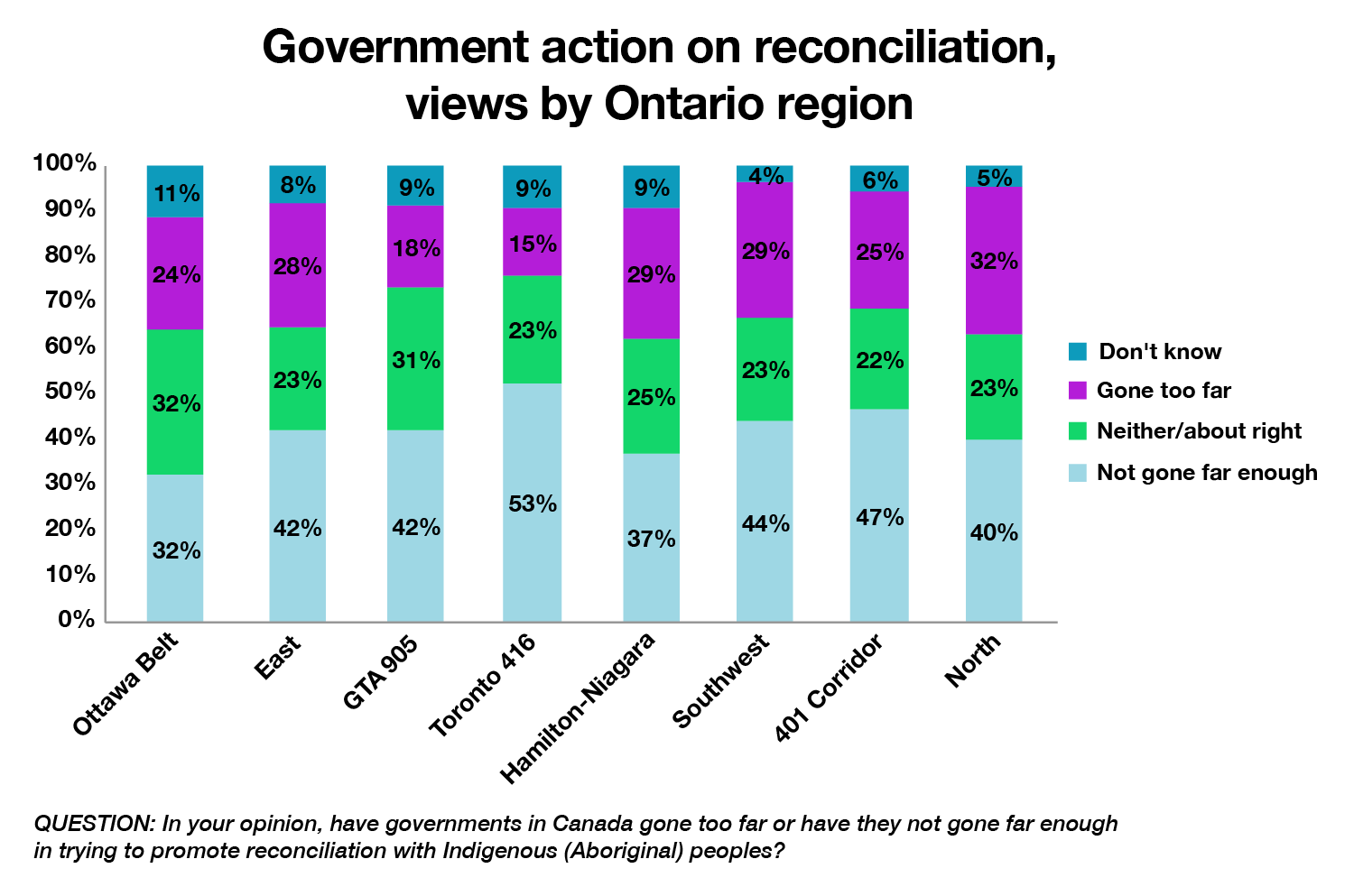

There is, of course, a proportion of the public that remains unconvinced. Twenty-three per cent, for instance, say they think governments have already gone too far to promote reconciliation, while one in ten say that the situation of Indigenous peoples in Canada is actually better than that of other Canadians. These responses should not be dismissed, but there is no basis upon which to claim that they come close to reflecting the views of the majority. Indeed, in every region of the province, the number of people who say that governments have not gone far enough to promote reconciliation outweighs the number of people who say that governments have gone too far.

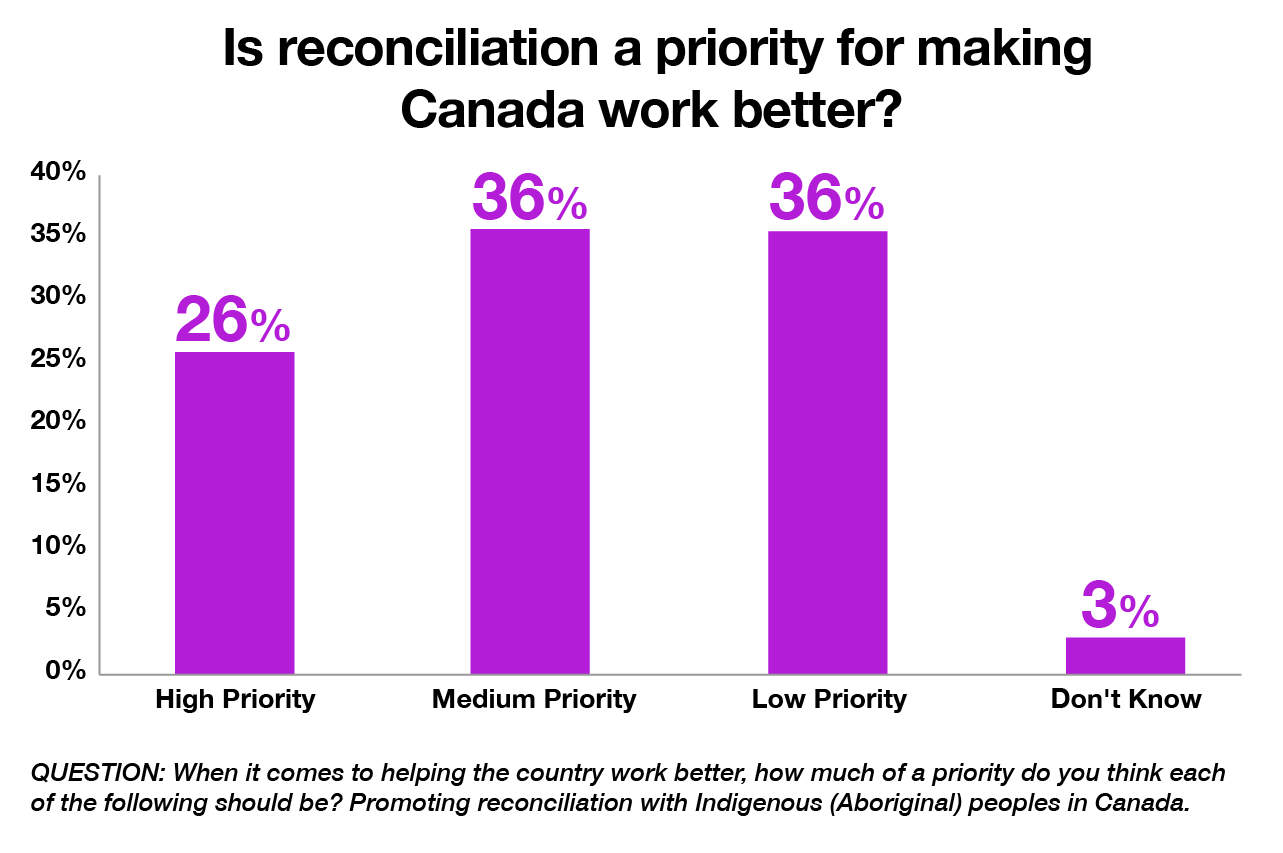

What is somewhat concerning, though, is an apparent lack of urgency. When Ontarians are asked about their priorities for making the country work better, promoting reconciliation with Indigenous peoples in Canada is far down the list. Spending more on health care is most frequently cited as a high priority, followed by being economically competitive, reducing inequality, and addressing climate change. Far fewer Ontarians – only one in four (26 per cent) – say that reconciliation is a high priority for making the country work better. Significantly more say it is either a medium (36 per cent) or even a low priority (36 per cent).

These results suggest that the issue of reconciliation, while gaining support, has yet to move into the political mainstream. Citizens’ attention tends to focus on the services most of them receive and the taxes they pay for them, and not on the urgency of addressing the legacy of Canada’s shameful track-record of relations with Indigenous peoples.

The survey provides additional clues both about the problem and the way forward. Gender is a factor, with women being more likely to prioritize reconciliation (32 per cent of women, but only 20 per cent of men, see reconciliation as a high priority; 45 per cent of men, but only 27 per cent of women, see it as a low priority). Older men in particular are less supportive, with one in two men aged 50 and over saying that promoting reconciliation with Indigenous peoples is a low priority for making the country work better, and 38 per cent saying that governments have gone too far to promote reconciliation.

40 per cent of women and 31 per cent of men who feel that Canada’s economy has improved over the last five years say that reconciliation is a high priority, compared with only 27 per cent of women and 11 per cent of men who feel that the economy has worsened.

Those more worried about the economy are also less supportive: 40 per cent of women and 31 per cent of men who feel that Canada’s economy has improved over the last five years say that reconciliation is a high priority, compared with only 27 per cent of women and 11 per cent of men who feel that the economy has worsened.

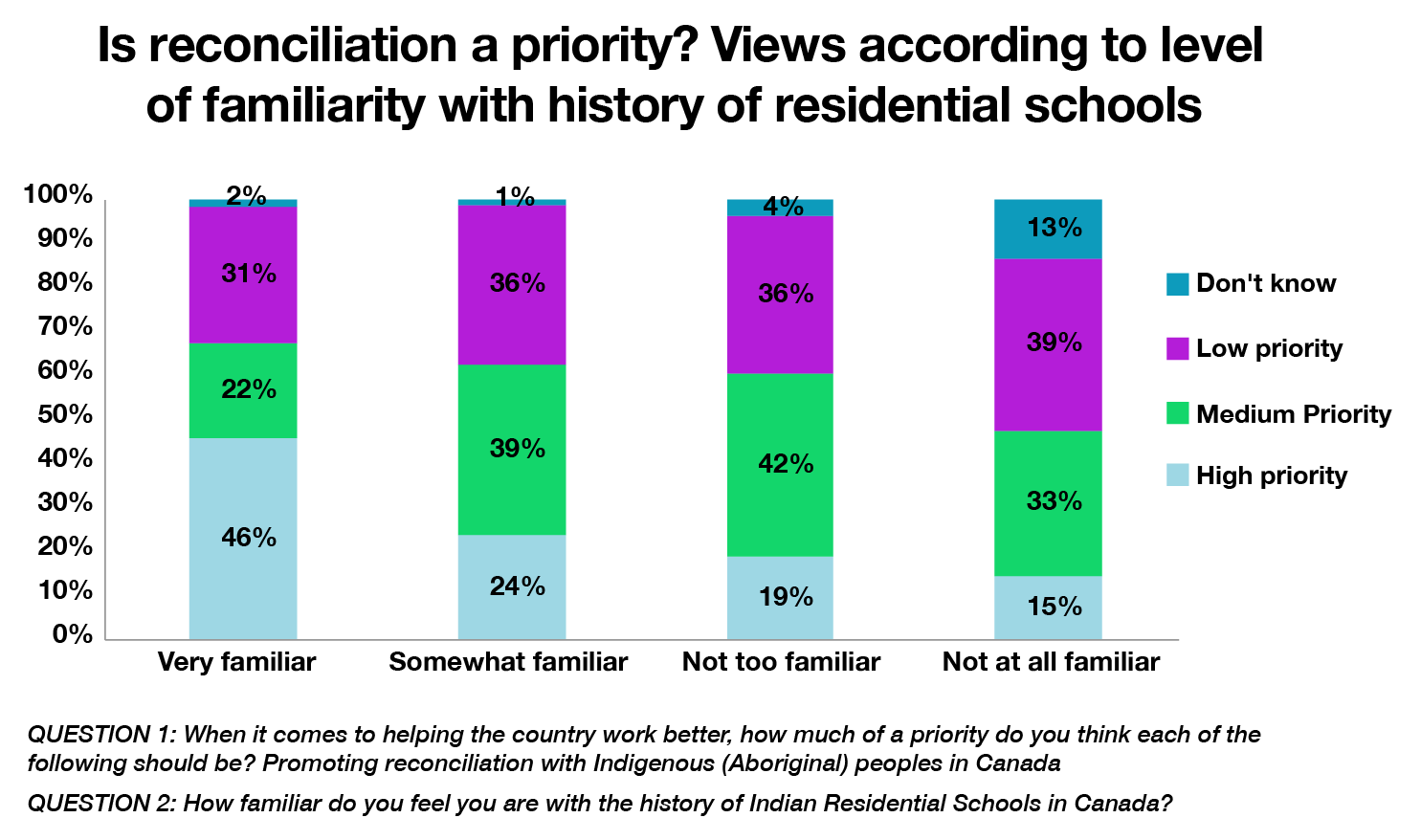

Tellingly, however, views on the urgency of reconciliation are also linked to awareness of the history of Indian residential schools. Those who say that they are very familiar with this history are more than twice as likely as others to say that promoting reconciliation with Indigenous peoples is a high priority.

This brings us back to the recommendations of the TRC. As the calls to action were released, Commissioner Chief Wilton Littlechild addressed Canadians by saying: “we are calling on you to open up your mind, to be willing to learn these stories, to be willing to accept that these things happened.”4

Since then, governments have taken steps to integrate education about the history of residential schools into the school curriculum. The survey results show why this is important, but also point to the need to engage everyone, and not just students, in the discussion. Three in ten Ontarians over the age of 30 say they are not too or not at all familiar with the history of Indian Residential Schools in Canada.

Thankfully, there is no evidence of polarization – something that would make progress even more difficult. Our survey data point not to a deep rift over the need for action on reconciliation but to a lack of a shared sense of urgency. This means that beyond government action – however important – there is also the need to continue to engage and educate citizens as to the reasons why, as Chief Littlechild reminded us, reconciliation “is not an Aboriginal issue, it’s a Canadian issue”5 – an urgent priority for everyone.

Author

Andrew Parkin

Release Date

Jan 10, 2018

- Barrera, Jorge. “Sen. Lynn Beyak’s son, a city councillor, says Conservative leadership cowed by political correctness.” CBC News. January 5, 2018. http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/nick-beyak-defends-mother-senator-lynn-beyak-1.4475445. [↩]

- Portraits 2017 is a public opinion survey undertaken by Mission Research on behalf of the Mowat Centre. Survey data were collected between November 1 and November 14, 2017 from within randomly-selected, representative samples of 2,000 residents of Ontario. The sample frame was drawn from opt-in market research panels and hence samples cannot be technically characterized as random probability samples. Still, as a guideline, an appropriate margin of error for the sample is +/- 2.2%, 19 times out of 20. The data are weighted according to the most recent Census figures for age, gender and region. [↩]

- Government of Ontario. “The Journey Together: Ontario’s Commitment to Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. One-year progress report June 2017.” https://www.ontario.ca/page/journey-together-one-year-report. [↩]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. “TRC releases calls to action to begin reconciliation.” June 2, 2015. http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/TRCReportPressRelease%20(1).pdf. [↩]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. “TRC releases calls to action to begin reconciliation.” June 2, 2015. http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/TRCReportPressRelease%20(1).pdf. [↩]