December 22, 2015

On Sunday, the federal government announced the details of the major transfer payments to provinces and territories for the next year.

This annual holiday tradition has been the subject of some anticipation and speculation this year, mostly focused on how changing economic fortunes would influence what each province would receive. Here are the questions some of you are asking about the recent announcement, and what we know so far.

What are the major transfers?

There are four main programs that we think of as the “major” federal transfer payments to provinces and territories. Two of these programs — the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) and the Canada Social Transfer (CST) — are the legacy of the federal government’s contribution to creating our major social programs, such as health care and social assistance. These two programs combined represent 70 per cent of the nearly $71 billion in major federal transfers announced for 2016-17.

The remaining two programs are designed to help provinces and territories deliver reasonably comparable public services at reasonably comparable tax rates. The Territorial Formula Financing program ($3.5 billion) helps the three territories, while the Equalization program ($17.8 billion) goes to provinces with below-average capacity to raise revenue.

If you would like even more of a primer on transfer payments — and who wouldn’t? — read this.

Who is getting what next year?

Some in the media have referred to the new Minister of Finance’s “decision” to boost transfers giving to the provinces. But in fact, all four of these transfers are calculated based on data-driven formulae that were established years ago, and have not been changed by the new federal government. The only reason there was suspense is because new economic data had to be fed into the models.

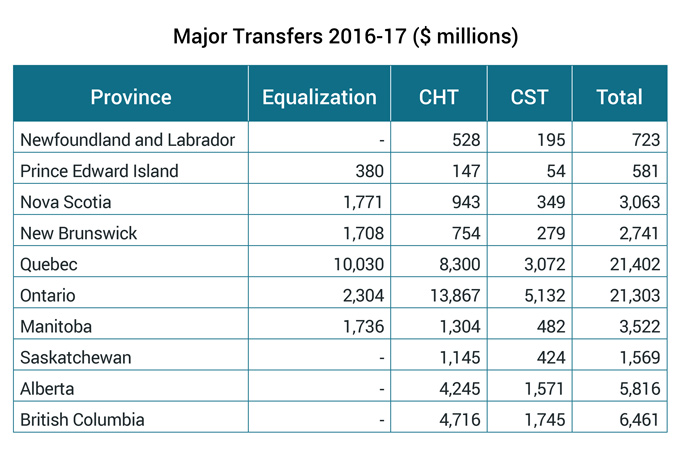

Provinces will each receive their per capita share of the CST and CHT and will receive a share of Equalization based on their fiscal capacity over the previous three years.

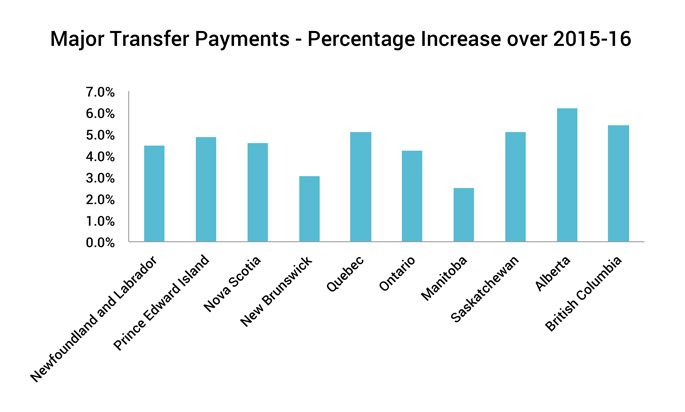

Every province is receiving more in both absolute and per capita terms than they did last year. Those increases range from a low of 2.5% in Manitoba to a high of 6.2% in Alberta. In fact, Alberta, Saskatchewan, British Columbia and Quebec are seeing the largest year-over-year increases in transfers, despite the fact that the Western provinces will receive no Equalization payments this year.

Every province is receiving more in both absolute and per capita terms than they did last year. Those increases range from a low of 2.5% in Manitoba to a high of 6.2% in Alberta. In fact, Alberta, Saskatchewan, British Columbia and Quebec are seeing the largest year-over-year increases in transfers, despite the fact that the Western provinces will receive no Equalization payments this year.

That might seem surprising given that the news coverage has focused on the Equalization program. It shouldn’t be. It is well known that all of these programs are set to grow each year, and that the CHT and CST are distributed based on population size. The fact that the three western-most provinces and Quebec were receiving the largest increases should not have been news when it was announced on Sunday.

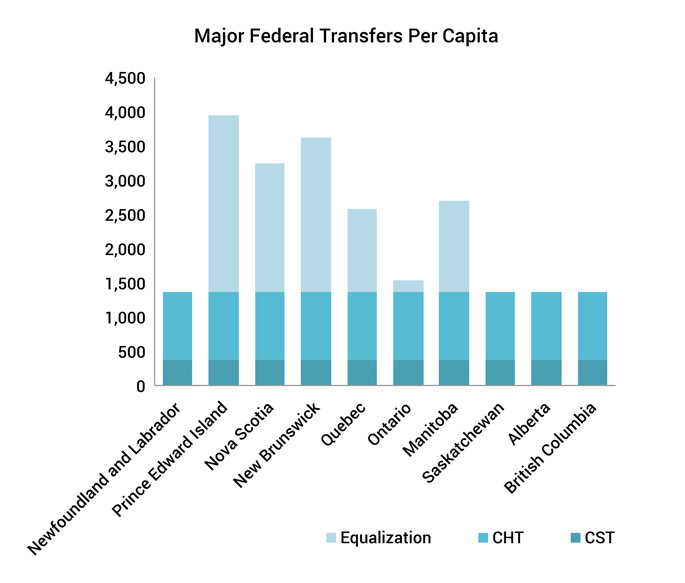

Because the CHT and CST are now distributed on an equal per capita basis, the differences between what provinces receive can be explained only by the size of their population (and its rate of growth), or by the Equalization program. Support to Equalization-receiving provinces will range from $166 per person in Ontario to $2577 per person in Prince Edward Island.

Given low commodity prices, why aren’t we seeing more of a change in Equalization?

Over the course of the past year, we’ve heard quite a bit about changing economic fortunes in Canada, as Ontario is expected to have among the strongest economic growth in Canada, while Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador have faced the shock of a sudden decline in commodity prices.

There are three main factors that explain why we only see this reflected in a muted way in the latest transfer payment numbers.

- Thanks to changes in 2007 for the CST and 2014 for the CHT, these two transfers — more than two-thirds of the total — are allocated on a strict per capita basis. That means that changing economic fortunes play no role one way or another.

- The federal government only counts 50 per cent of natural resource revenues in the formula for Equalization. This means that the effect of any change in natural resource revenues will reduced.

- The formula for Equalization payments is calculated on a rolling three-year average to smooth out sudden spikes, with a two year lag. This means that for next year’s payments, about 2.5 years of very high oil prices are currently being factored in alongside the more recent decline. It also means that if oil were to return to $100/barrel tomorrow, today’s low prices would be considered in the formula for three more years.

It is clear that commodity prices are major drivers of the difference in fiscal capacity between provinces in Canada. Surging commodity prices were the major reason that Ontario fell below the average fiscal capacity line and began to receive Equalization payments, and the decline in prices will likely bring that average down and bring an end to Equalization payments to Ontario.

Is Alberta going to receive Equalization in a few years if oil prices remain low?

No.

Even in tougher times, Alberta remains far wealthier than other provinces. Equalization payments are based on the average fiscal capacity of provincial governments. Other contributions to fiscal capacity, like provincial income taxes, are simply much higher in Alberta than elsewhere.

In the medium term, nothing short of a shock at the level of a ninja zombie invasion is going to bring Alberta below that average. Conversely, nothing short of discovering that Cape Breton is literally made of diamonds will bring Nova Scotia above the average.

With that in mind, it’s also important to point out that resource-rich provinces are not “continuing to pay into the program” despite tough times, as some news stories have put it.

Provincial governments don’t make Equalization payments, the federal government does. Or to put it differently, Canadians do. Albertans do send more to Ottawa than comes back to the province, on net. So do Ontarians. Whether or not a province receives Equalization payments is only one slice of this equation.

As we’ve said, well a few times, this is what we get with a skewed Equalization program that doesn’t adequately address differences driven by commodity cycles.

What about Saskatchewan?

That’s a different story. As we’ve said elsewhere: “Whether Ontario or Saskatchewan receives Equalization ten years from now will depend largely on the internationally determined price for commodities like oil and potash. A commodity boom—or bust— says nothing about the moral worth or economic policies of either Ontario or Saskatchewan”. During the oil boom, Saskatchewan’s fiscal capacity rose above the national average and Ontario’s dropped below. A period of sustained depression in commodity prices will likely reverse that pattern.

The Premier of Saskatchewan has suggested the Equalization formula is unfair to Western provinces? What is he talking about?

The Premier of Saskatchewan has been voicing concern about a technical issue in Equalization, identifying the rolling average and 2-year lag that exists in calculating fiscal capacity as unfair to Western Canadians: “Why this lag for Western Canadians?” This complaint is off-base, as this is neither a policy that harms Western provinces, nor is it one that only applies to Western provinces.

That lag exists because provinces asked for it so that their revenues were more predictable and stable. In 2007, the federal government agreed to use what is called a three year “rolling average” to calculate all provinces’ fiscal capacities, to smooth out the revenue cycle for all and avoid wild fluctuations. Essentially, all provinces receive the same amount they would receive if no lag was used – just in later years, which makes fiscal planning somewhat easier.

What the lag means in practice for Saskatchewan is that as their resource boom took off, the province continued to receive Equalization payments even when its fiscal capacity was above the national average. Likewise, Ontario did not receive Equalization payments right away even as its fiscal capacity fell below the average during the commodity boom.

So is Ontario on the verge of no longer being a “have not” province?

Ontario was never a “have not” province. The distinction between “have” and “have not” is one that we reject and that conceptually makes little sense.

Whether a province receives Equalization or not is based on many historic and economic factors. It is inherently relative. Even if all provinces are doing extraordinary well – or extraordinarily poorly – economically, some will have lower than average fiscal capacity — that’s how averages work. In Canada, whether a province is above or below that average is heavily influenced by their endowment of natural resources and the price of those resources on global markets.

There are some who want to claim that receiving Equalization is a useful signifier that the economy of a province sucks , or that “getting off Equalization” is a testament to the wise economic policies of the provincial government. We think these analyses are just silly.

As we’ve said before: “[Most provinces] will not have higher fiscal capacity than Alberta or Ontario in the conceivable future, regardless of how well [their] economy is performing or how hard [their] people are working. The equivalence in Canadian political discourse between “poor,” “have not,” and “Equalization-receiving” distorts our national conversation.”

Why are some provinces pushing for changes to the Canada Health Transfer formula? Don’t they have a point?

There are reports that some provinces are looking to discuss a change to the way the Canada Health Transfer is distributed. This one is all about the Benjamins.

As of 2014-15, each province gets a share equal to its share of the population, a change that was many years in the making. Those provinces, generally the ones of Ontario, are arguing that there should be greater weight given to citizens 65 years and over. Unsurprisingly, support for this particular change correlates strongly with which provinces have the oldest populations.

While need-based funding can be a legitimate approach to allocating transfer payments between provinces, this is not the way to do it. A real need-based formula would likely take into account the real cost of delivering health care services, and other population indicators that shape the needs and cost for health care delivery. Cherry-picking one demographic characteristic to introduce into the formula, while ignoring all the others that might lead to different calculations, is not sound policy.

So this proposal is not really about the way that we fund health care, it’s quite nakedly an attempt by some provinces to squeeze more out of the pie at the expense of others.

Author

Noah Zon

Release Date

Dec 22, 2015